[This October is "Gialloween" on Daily Dead, as we celebrate the Halloween season by diving into the macabre mysteries, creepy kills, and eccentric characters found in some of our favorite giallo films! Keep checking back on Daily Dead this month for more retrospectives on classic, cult, and altogether unforgettable gialli, and visit our online hub to catch up on all of our Gialloween special features!]

If there's one immediate connection one can establish between the Italian giallo and the traditional American slasher, it's that both have been on the end of pointedly barbed criticism. Popularity, of course, has never been an issue, but cultural gatekeepers have had their knives out for the slasher from day one, while the giallo has often been decried as nothing but violent misogynism told through incoherent plots. Even the original Mondadori novels from which the genre takes its name were denounced by Mussolini's fascist government—you couldn't ask for a better recommendation. But the other connection? Music.

In contemporary times and the advent of the DVD and more advanced Blu-ray, audiences have had access to the giallo like never before, meaning they can not only see these pictures almost for the first time, but also hear them, both of which have contributed to a reassessment of the giallo as art. Together, the giallo and the slasher have been a major part of the resurgence in film scores and soundtracks on the vinyl format, with a particular interest in music coming from horror cinema. Therefore, we now have the likes of Ennio Morricone, Stelvio Cipriani, and the infamous Goblin sharing record store shelves with John Carpenter, Harry Manfredini, and Charles Bernstein. This is but a surface look at how one influenced the other.

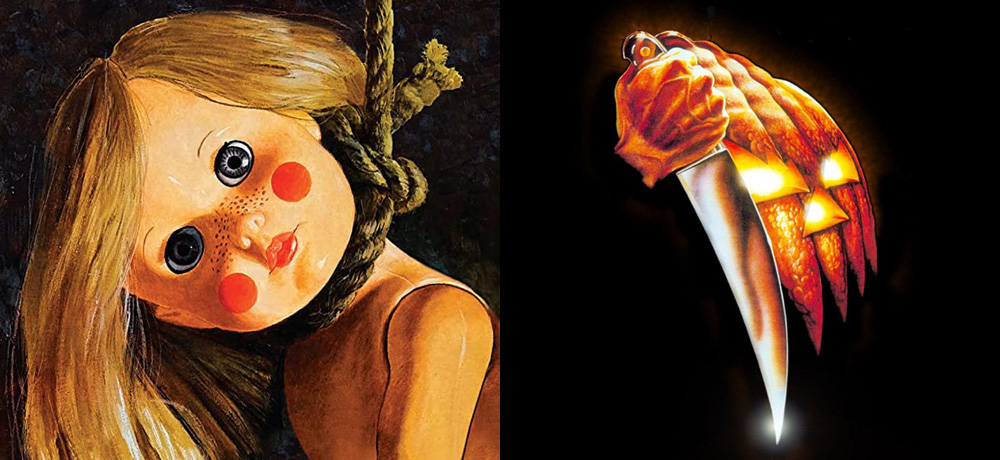

Nevertheless, if you expected to be regaled with the classic music of the gialli by watching the film that is credited with starting the giallo as a cinematic genre, Mario Bava's The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963), you'd be forgiven for wondering if you had put on the right film while listening to Adriano Celentano crooning “Furore” over the opening credits. Likewise, Roberto Nicolosi's traditional score, while fine, does not exhibit any qualities that would ally it with the music of the giallo. But it was Bava's subsequent film that would cement not only the cinematic tropes of the genre, but the musical ones too, with Blood and Black Lace (1964) and its main theme “Atelier,” the full-blooded dose of sleaze-jazz riff that runs over its mesmerising opening titles.

The score to Blood and Black Lace was composed by Carlo Rustichelli, who was known as the father of Italian film music. Interestingly, Rustichelli used fragments of “Atelier” in the film's death sequences, together with contrasting high and low scales, with strings moving from one extreme to the other within seconds. With this method, the audience feels the heightened score as the camera is fixed on the victim, emotionally connecting the two before one is forced to watch the other suffer violently. In the film's second murder, the music stops until we see the killer bring out his strange three-pronged weapon, at which Rustichelli scores the weapon itself, rising and rising in tension with a final trip up the scales as the victim is stabbed in the face, the score ending immediately.

In John Carpenter's Halloween (1978), the first murder is of the killer's sister, Judith. With the point of view established as being from the killer's perspective (a mechanism used as far back as 1946 with Robert Siodmak's The Spiral Staircase), the scales descend before being usurped by a droning synth line, again showing the murder weapon. The synth line is used again as murders are committed, a stripped-down and minimalistic equivalent very much of the era it was created in, where the Moog synthesiser was all the rage. Later on, when final girl Laurie Strode is being stalked by "The Shape," Carpenter's keyboard plays both low and high tones to ratchet up the tension—like Rustichelli.

But also influencing Carpenter was Goblin, the prog-rock outfit that came together for many of Italian wunderkind Dario Argento's movies, as well as George Romero's Dawn of the Dead. And while it was their black forest magic masterpiece Suspiria that had a palpable influence on Carpenter, they had already owned the giallo in the form of their score for Argento's Profondo Rosso (1975), which takes the prog and metal influences of bands like King Crimson and Black Sabbath and applies them to the visceral death sequences, creating an assault on the audience as well as the victim. The theme for the scenes is appropriately named “Death Dies,” and it's a wild journey with a jazz-fusion feel from the percussion, deep bass, and a frenzied harpsichord line as violent as the murders themselves, affording the scenes an edge that has seen Profondo Rosso frequently celebrated as the ultimate giallo.

Similarly, Tony Maylam hired Rick Wakeman to write music for his 1981 slasher The Burning. Wakeman had been a member of British prog-rock band Yes in the early 1970s before going solo with an orchestral rock concept album called Journey to the Centre of the Earth, based on the Jules Verne novel (and narrated by Profondo Rosso actor David Hemmings). Wakeman's fierce synth arpeggios recall Goblin's own "wall of sound" approach and are fairly effective, even when Maylam's film clearly can't match the artistry of Argento's, and it feels like a child of both Goblin and Carpenter, as well as another Italian music great, Fabio Frizzi, famous for scoring films for Lucio Fulci.

And then, of course, you cannot talk about the music of gialli without mentioning the late Ennio Morricone. The maestro's work in film has long featured unique vocalisations, particularly in his famous spaghetti western scores, but they also make it into his giallo output, particularly the 1972 Aldo Lado film Who Saw Her Die? that has Morricone using the voices of children in a visceral and frankly psychotic fashion. This trope has certainly found itself into various horror genres (including the composer's own Exorcist II: The Heretic), but notable slasher entries include Jonathan Elias' 1984 supernatural slasher Children of the Corn, which features a cacophony of chanting children as they do various horrific things to adults.

There is one aspect of the music of gialli that perhaps has not attached itself to the slasher, and that is the absolute beauty that often comes with it, from Morricone's wonderful melodies to Cipriani's simply gorgeous pieces, this is a focus that deserves more future scrutiny. But until then, look further into the musical connections between Italy and America and the giallo and the slasher, for they are not only many, they are also as rewarding as you may imagine.

---------

Keep an eye on our online hub throughout October for more of our Gialloween retrospectives!