Longtime readers of Daily Dead and listeners of Corpse Club know that our love of Clive Barker's Hellraiser cinematic universe is as undying as Pinhead's pleasure in pain, so we were especially intrigued to see that the Discord server for the Hellraiser: Revival video game recently hosted a compelling 56-question interview with Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski, the screenwriters behind 2022's Hellraiser reboot!

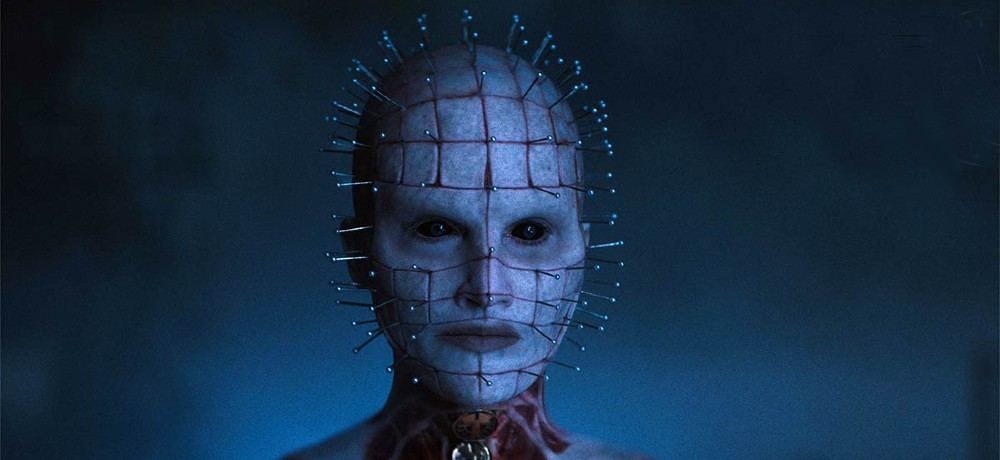

Daily Dead was graciously granted access to the extensive interview with Ben and Luke courtesy of Tony Searle of the Hellraiser Discord Community, and it's a true treasure trove of behind-the-scenes insights into the development of Hellraiser (2022). Suffice to say that this comprehensive deep dive certainly has "such sights to show you" when it comes to how Ben and Luke summoned their script for the Hellraiser reboot, including their new take on Pinhead (aka The Priest, played by the amazing Jamie Clayton), their unique approach to the puzzle box configurations (including Lament, Lore, and Laudarant), what they would love to explore if they were ever given the opportunity to write a sequel, and much more!

We've selected some of our favorite highlights from the Discord discussion below. For more fascinating details, we highly encourage you to check out the full conversation with Ben and Luke, as well as other insightful interviews with key figures in Hellraiser history (including Butterball actor Simon Bamford), by visiting and joining the Hellraiser: Revival Discord page and checking out their YouTube channel:

Interview Excerpts Courtesy of Tony Searle - Hellraiser Discord Community

How did you both first get involved with the Hellraiser project, and what excited you most about taking it on?

Luke Piotrowski: Back when we were fairly unestablished screenwriters, our agent and manager got us a call with the people at Miramax who had the rights at the time. As children of the 80s, we were thrilled to have the chance to play with some of the most sacred franchise toys. We crafted a pitch. It was NOT what they were looking for. But, for years, Hellraiser sort of felt like the one that got away. And our individual passions for the franchise became a special point of connection between us. It was the one we both loved and desperately wanted to do. Somehow, someway.

Cut to many years later, we were making The Night House with David Goyer’s Phantom Four when we heard the news that they were working on the title with Spyglass. We shamelessly went right to our friend Keith Levine, creative producer at Phantom Four. “So… what’s up with Hellraiser?”

There was a bit more to it than that. We had to have creative discussions with them and craft some documents before being brought in to pitch to Spyglass. But as far as landing a gig in Hollywood goes, it was one of the most seamless.

I think what excited us most was probably what excites everyone here on this discord. Hellraiser is horror but it’s also something more. It has some of the most extreme violence in the genre, but also a sense of gothic poetry. A sense of the theatrical. And a mythology that is dense and evocative. Some of the most striking and elegant production design too. Of all the horror franchises, Hellraiser is the most literary. That’s something I respond to.

Ben Collins: I have a very distinct childhood memory of seeing the VHS cover of the original Hellraiser film in a video store and being both terrified and hypnotically entranced by it. I was probably 5 years old and certainly unable to read yet. But the image of Pinhead was seared into my brain and took on a mysterious mythical quality in my childhood. I didn’t see the film until I was about 10 years old and found it playing on a local broadcast station one night. Even then I think I only saw maybe half of it. Mostly I remember seeing Frank’s regeneration sequence and having to turn it off when my parents got home so I didn’t even get to see Pinhead. Years later when I was a freshman at art school my roommate in the dorms had a DVD copy and it was the first movie we watched together on the first night we spent away from our parents.

It wasn’t until 2010 or 2011 when Luke and I were first contacted by executives at Dimension Films as part of a cattle-call for screenwriters they could hire to reboot the various franchises they controlled at the time. Luke and I were both immediately interested in Hellraiser and started daydreaming about how we might be able to play in that world in a way that could bother honor what we loved about it, but also bring it to a new audience with a level of prestige that had been lost in the franchise over time.

Of course we didn’t get the job at that time. And for years Hellraiser was the one that got away. Over the years different companies would claim to have the rights and we would meet about it. But it wasn’t until 2019 that Keith Levine from Phantom Four reached out directly to us about potentially getting involved in writing the movie that became Hellraiser 2022.

So it was a really long path but I think for me personally part of what continued to drive my interest was the desire to access that feeling of awe that I had as a child looking at the cover for the first time.

When approaching a beloved horror franchise, what were your first discussions about tone and direction?

Luke Piotrowski: We had a long-running joke right from the start that any reboot of Hellraiser needed three things: sex, death and puzzles. If you take any one of them away, it isn’t Hellraiser anymore. Just puzzles and death? That’s Saw. Just sex and death? That’s most horror movies. Just sex and puzzles? That’s close… but not quite.

Personally, I think tone is incredibly important when it comes to making additions to any franchise. It’s so important to dump out the box of components and see what something really is at its heart. What makes it work.

That’s doubly important with Hellraiser. Barker’s work is so much about tone. Not just what’s happening but the way that it’s presented. The grotesque and the sensual are serviced in equal measure whether on screen or on the page.

At one point, a different set of producers actually got hold of the rights and approached us. But they only cared about the title, not the tone. They wanted something with hot teens, a slasher sort of thing. And we ultimately just said “no thank you.”

To us, Hellraiser couldn’t be a slick slasher. It’s not a “hell yeah” movie. It’s not even a heavy metal movie. It’s gothic elegance laced with putrescence. A beautiful, dangerous nightmare.

Ben Collins: I think we always like to ask ourselves “what are the most essential parts that make this thing what it is?” So the discussion starts with understanding what pieces we’re working with, and understanding the history of the franchise and what’s been done before. In a case like Hellraiser it’s fun to watch all of the old movies and kind of take stock of what works and what doesn’t, or in some cases what could have worked, all of which can point you in the direction of what hasn’t been done yet.

So the process becomes negotiating that feeling of being true to what it is but also introducing new things it can be.

Did you revisit Clive Barker’s original novella The Hellbound Heart during development, and if so, how did it influence your writing?

Luke Piotrowski: Many times. Hellbound Heart, In the Flesh, Damnation Game, Scarlet Gospels. Even the old Hellraiser comics! As soon as it started to become real, I began steeping myself in Barker again. I wanted more than anything to evoke those vibes. To be in that headspace.

There were many elements from the novella we tried to incorporate into the movie, particularly when it came to the Cenobites. A lot of them fell away during the road to production, unfortunately. But I want it on the record that we fought hard to keep the jars of piss Frank planned to use to anoint himself! We also had the sound of wings and birds that the book describes when the Cenobites appear but it became one element too many and we landed on just the bells.

Ben Collins: I’ve read Hellbound Heart a few times over the years, as well as listened to multiple audio versions, (included a wonderful, abridged version read by Clive himself on YouTube) so it was very much on my mind throughout. Luke and I talked about it extensively and felt the book’s descriptions of the Cenobites gave us a lot of latitude in terms of how to imagine them in a new version.

Was Clive Barker involved in your writing process, and if so, what was the most valuable feedback he gave you?

Luke Piotrowski: Unfortunately, we never got to meet or talk to Clive himself. I know he was in contact with director David Brucker quite a bit, though. That’s my one big regret, that we never got the chance to collaborate with him. Even if only a little. I do know he specifically wanted to address Riley’s faith or lack thereof, which I thought was interesting and led to some discussion and some different dialogue.

You’ve mentioned that your version of Hellraiser was inspired in part by earlier pitches and ideas, and that some work you did for ‘The Night House’ grew out of discarded Hellraiser material. Are you able to detail what the original Hellraiser pitch looked like?

Luke Piotrowski: The short version is we wanted to do a very elegant, very hallucinatory version of The Hellbound Heart. Very Black Swan. What fascinated us about the original story and film was that Julia is in many ways the real protagonist. Kirsty is sort of the damsel in distress and the climax rests on her shoulders but most of the really juicy, emotional stuff and a great deal of the conflict falls on Julia. That initial pitch basically merged the two characters into one. The task we gave ourselves was to craft a more tragic, sympathetic version of Julia.

In our take, she was a woman who was still reeling from the sudden death/disappearance of her husband. While investigating what happened to him, she discovered that she didn’t know him quite as well as she thought she did. He had a secret side, a secret life. Secret desires that he pursued via the occult. In short, she thought her husband was a Larry. After his death, she discovered he was a Frank.

It was the puzzle box and the Cenobites who claimed him, of course. She solves the box and uses it to bargain with the Cenobites to bring him back. They agree… but what they return is not the husband she remembers. Very much like Frank in the original film, her husband comes back a tattered and bloody husk, tortured beyond recognition. Like any deal with the devil, it gave her what she wanted but it led to her damnation. In order to restore him, she had to start going out, stalking men, bringing them back to kill and feed him. It was very much a story about a woman mad with grief, trying to numb herself with violent and meaningless sex. And also a story about following a loved one down a dark path. Trying to fill a hole in your soul. Sort of a Lars Von Trier movie in a way.

The plan was for her to ultimately renege and try to break the deal, incurring the wrath of the Cenobites. But it was all very dark and elevated and not really anything financiers would be willing to make! I still think it could be incredible, though.

We ended up taking the ‘grieving widow makes a dark discovery about her husband’ conceit and using it as the engine of Night House. The earlier drafts of that one were also much more sexually charged.

How did those earlier ideas evolve and inform the final version of Hellraiser (2022)?

Luke Piotrowski: Ultimately, we weren’t able to take too many concepts from that initial pitch into the 2022 film. When we came on board, David Goyer already had a rough treatment. It was only a few pages long but it outlined an engine that was totally different from ours. That was the foundation we built 2022 on.

The one thing that carried over from our earliest conversations was the notion that maybe the puzzle box could offer rewards other than incredibly brutal torture. The pain/pleasure line is, of course, interesting. But it’s so extreme that it can be hard to craft a narrative around. We knew we wanted to be able to motivate people to risk using the box for other reasons. To allow for protagonists that weren’t all like Frank while still keeping those elements alive and well.

How did you balance honouring the franchise’s mythology and established canon whilst creating something fresh for modern audiences?

Luke Piotrowski: We felt a great responsibility with the mythology. Our hands were tied somewhat by having a treatment already in place. But I think we got to do most of what we wanted to do in terms of adding to the canon.

We had some discussions about trying to approach it in such a way that we didn’t flat out contradict any of the existing mythology so as to perhaps allow it to exist within the extant canon. Ultimately, we had to diverge, though. From a design standpoint, it just ended up being too unique. And the new rules regarding the configurations made it clear that this had to be its own, fresh continuity.

Ben Collins: I think for me part of why I wanted to work in the Hellraiser franchise was precisely because the canon mythology is fairly convoluted as a result of there never being a consistent authorial voice dictating the decisions between the films. For as much as I love some of the sequels (Hellraiser III is arguably my favorite of the franchise up until Pinhead shows up at the club) they seem to have each been made in service of themselves as opposed to much of an overriding mythological consistency. This is not anyone’s fault of course, the movie industry was very different when Clive made the original film.

But for our purposes the inconsistent mythology provided the opportunity to rebuild a version that incorporated aspects of many of the individual films, as well as original novella and some of the other extended universe stuff. More than anything we wanted a version of the Hellraiser mythology that both worked in our film, but could also be carried forward in subsequent films, whether by us or anyone else. I think we were successful on the first part and time will tell about the second part.

The Hellraiser mythos is extensive, with many movies, books, and comics. When you were approaching this reboot, what core elements did you feel were essential to retain, and which parts did you feel needed updating or reimagining for modern audiences?

Luke Piotrowski: Obviously, we had to have the box. Had to have a Pinhead. Had to have the chains. Ben and I knew we wanted to pull in some Hellbound elements too. We wanted the labyrinth, we wanted Leviathan.

I think what’s essential is that concept of “angels to some, demons to others.” The Cenobites aren’t monsters or maniacs or killers. They really are trying to share their gospel, to offer you gifts. It’s not their fault if you don’t appreciate those gifts. Pain is beautiful to them. Divine.

I also think it’s essential that Pinhead be able to communicate. Early on, there was sort of an edict to keep Pinhead more like the Night King from Game of Thrones. A silent, stoic figure. But what I love so much about Barker’s work is the point of view of the “monsters.” The original Candyman is so effective because that character is so seductive. “I am the whisper in the back of the classroom… be my victim.” I felt it was essential that Pinhead be seductive and allowed to try and sell their worldview. To give voice to an ideal.

Ben Collins: I think for me the most crucial distinction that Cenobites have over other horror movie "villains" is that they make decisions based on their own interests and desires. They speak and make statements about their opinions, and they can lie and break their own because they enjoy doing that. So any version that dumbs them down or makes them beholden to too “rules” can only diminish their power.

The idea of adding different functions to the box itself was something Luke and I discussed way back in 2012 because it seemed to us that the Cenobites would probably enjoy having multiple ways to trick, manipulate and torture people. So even though it was a “new idea” it still felt in-kind with the behavior of the Cenobites as consistently demonstrated in the lore.

The main thing I love about Hellraiser III is that the first half is just about these two women becoming friends while trying to solve a mystery together. So I think that aspect definitely inflected some of the first half of our movie.

Leviathan is my favorite thing in Hellbound, and I guess the architecture stuff is my favorite aspect of Hellraiser IV. As Luke said, a lot of pieces came with Goyer’s treatment, but it helped that all of us seemed to overlap enough on which things felt were worth pulling from.

What drew you to explore addiction as part of Riley’s arc, and how did you balance that with the supernatural/horror elements?

Luke Piotrowski: Once we started to pull away from the grief aspects (thank God, because it was already very played out even several years ago), it was a no-brainer to dive headlong into Riley’s addiction and self-destructive behavior.

It got a little lost in the translation to screen but, to me, Riley is a dominant personality that wants to be submissive. Like many addicts, she hates herself and the things she does but everyone in her life is so accommodating they are unable to offer the punishment she craves. She has no tools to absolve herself of her sins, so she just ends up hating and punishing herself more.

She’d like nothing more than for her brother to call her on her bullshit. When he kicks her out of the house at last, it’s a sort of relief. Fucking finally! She even has to direct him, instruct him in how to yell at her. “Say it like you mean it. GET OUT! Like that.” She’s taking the cat o’ nine tails out of his hand and showing him how to swing it.

The supernatural elements were meant, of course, to evoke all these feelings and desires. Some of us don’t think we deserve anything but pain. It’s what we secretly crave.

How do you see her after the events of the movie? Is there a form of canon that you have for where she goes and what she does in the future?

Luke Piotrowski: I think it’s just like Pinhead says: she has to live. To carry that weight. For me, conceptually, every “reward” the box offers is a type of pain. It might be physical, intellectual, or emotional. But it’s always pain.

Once you’ve opened the box, you are fucked and there is no winning. Riley may not be having her skin ripped off within the Leviathan… but she is still going to suffer in a way that is just as interesting to the Cenobites.

It’s a dull, slow, pain. The ache of her guilt. The burden of her knowledge. That was always the ending we wanted to drive toward. The Lament Configuration is such an evocative name. I wanted to embrace that.

So, what’s next for her? The same as any addict, I imagine. She has to own the damage she caused. Try to be better. But life is hard. Life is pain. She’s on the same road as the rest of us.

Ben Collins: I hope Riley is staying sober and going to meetings and therapy. I suspect she may also be active on conspiracy subreddits as well as being among the many people demanding the release of “The Voight Files”. I hope she finds some kind of creative outlet or something that can give her some peace.

The figure of Pinhead is iconic, with Doug Bradley’s performance being very influential. What was your approach to Pinhead in this movie - in personality, in philosophy, and in visuals? How did you think about the legacy and audience expectations while still making something new?

Luke Piotrowski: We wrote the very first drafts just imagining Doug. Even going so far as to put all of Pinhead’s lines in bold. Hearing his voice in our heads. But we all knew it probably wasn’t going to be Doug. And the worst thing would have been having someone do a Doug impression. So we knew it had to be different. As everyone has noted, The Hellbound Heart describes the character quite differently.

The quickest way to differentiate it was to go female. There’s a precedent for that in the comics, after all (Kirsty herself!). Subsequent drafts went more in that direction. But that didn’t really change how we approached the character. The lines and personality all pretty much stayed the same. It was more of a casting issue than a conceptual issue.

I will say our Pinhead did ultimately become less booming and stern and more sensual and seductive. But that was true from the start. I mentioned Candyman earlier and in some ways, I found myself channelling him as much, if not more, than Pinhead when it came time to articulating the Cenobites worldview. There’s some Gary Oldman Dracula in there too.

What I wanted was for Pinhead’s threats to Riley to almost operate as temptations. I wanted to get some Barkerian turns of phrase in the dialogue. In hindsight, the scenes between Riley and Pinhead could have been hornier. But then, that’s true of most scenes!

There are always going to be people that reject the new. Pinhead is tied to Doug more than other iconic horror characters for sure. But I think Barker’s concepts transcend a single performance. It’s too juicy to limit to one interpretation.

We all love Doug. I think the best way to uphold the legacy of the character he originated is to not try to recreate it, to instead go back to the book and work from there to make sure we aren’t stepping on his toes or stealing from his toolbox.

And I think Jamie is so alluring and curious and calculating and threatening. She crushed it. I wish her take had made a bigger impact culturally.

Ben Collins: I mentioned the story earlier about seeing the VHS box as a kid, and I’m not exaggerating when I say that it was so unlike anything my brain had ever imagined that it was closer to something otherworldly or even god-like than just being some guy in makeup. That said, as I got older and began to understand how movies are made, the limited resources Clive et al had on some of these films became more apparent. So when you imagine making a new Hellraiser movie, the first desire is to be making it with a cinematic style and approach that is a level above what the franchise had ever done. So it was understood by us that our approach to Pinhead had to be new and fresh in a way that was requisite to the intended scale of production. But I think the desire to elevate Pinhead to being as otherworldly and godlike was there from the beginning. In as much as it was possible I hoped the audience would see our Pinhead the same way I saw Doug’s version. But to do so means making it necessarily different.

Does Jamie Clayton’s exceptional ‘Hell Priest’ exist in the Labyrinth alongside Doug Bradley’s? Are they from the same order, or perhaps another sect?

Luke Piotrowski: Ultimately, we ended up compartmentalizing a bit and deciding to cordon 2022 off as its own, separate continuity. So while actively writing, we were mostly looking at this as a different universe with a different set of Cenobites.

I always imagine the Cenobites (in both continuities) as being pretty timeless. They’ve been around for ages and will be around for ages. So I don’t see them updating or altering their appearances and modus operandi much.

There could be different sects I suppose. It’s not that difficult to imagine ways in which the two Pinheads could interact. But it wasn’t something we were building in or accounting for as we worked on the film if that makes sense.Ben Collins: Luke is giving the accurate answer as to how we conceived the movie. But considering the vast possibilities the mythology suggests, it doesn’t necessarily preclude the idea of parallel realities, alternate dimensions etc. Or there’s also the possibility that Pinhead and the Cenobites appear in a way that is catered specifically to the person who summoned them. I believe it was our friend, filmmaker Elric Kane who suggested to me many years ago that in the 1987 movie the Cenobites wear black leather because that’s what Frank expected when he summoned them, because that would have been transgressive at the time. Of course, in the modern world BDSM gear is just as much fashion as it is indicative of a lifestyle, so naturally their appearance changes and becomes transgressive to the time and the person interacting with them.

None of these ideas were intended in the script and are not supported by the movie, but it’s fun to think about.

Were there other Cenobites designed or scripted that didn’t make it into the final edit of the movie?

Luke Piotrowski: The star Cenobites were always Pinhead/The Priest, the Gasp (who was initially called The Gape but got softened/censored… in grand Deep Throat/Cunt Throat tradition), the Chatterer, the Weeper and the Asphyx.

The Asphyx is the one I’m most proud of as that was wholly my idea. I wanted to include different kinks and types of “torture” in the designs. The breath-play/latex play Cenobite felt like such untapped territory. It was actually based on a dream I had years ago where I visited a theme park that had an attraction called “Clive Barker’s The Fitting” which was just a really claustrophobic and upsetting vacuum sealing experience!

The biggest thing we lost (and it still bums me out) was a sequence Bruckner came up with where the Weeper split open completely and became a sort of quadrupedal creature. There’s production art of it out there somewhere I believe… or there might be on the upcoming German Blu-ray release. It was incredibly cool but had to be cut for budgetary reasons.

The movie makes some bold choices with the puzzle box configurations. Can you walk us through your reasoning and the ideas behind now needing the box to “cut” the solver and no longer needing the ‘desire’ element from the original conception?

Luke Piotrowski: The box is, and always has been, a trap of sorts. Frank thought he desired the “pleasures” it contained… but he didn’t. It was more than he bargained for. It is, at its core, a deal with the devil conceit. The devil promises something you want. And provides it… but not in the way you wanted.

Goyer’s treatment had an element of having to offer multiple sacrifices to the box. We liked the idea that the box was ultimately harder to “solve.” In the original films, it seems pretty simple. You rub the circle and out pop the chains.

The treatment suggested the possibility of a puzzle box that could take the entire movie to open completely. That was appealing to us.

We wanted the box to feel dangerous any time someone held it. It has the ability to essentially “bite” you. Any time a character held the damn thing, we wanted the audience to sit up. Ideally, I wanted to make it so that if you were to see a prop or replica of the box in real life… part of you wouldn’t want to touch it.In the end, it’s not all that different from the hooks in the original films. In the first movie, Frank has to obtain the box and solve it to get his prize (the extreme sensations). It opens and hooks and chains emerge.

In our version, if you want one of the prizes (including but not limited to extreme sensations) you have to obtain the box and solve it. Instead of chains immediately coming out, the blade pops out. The game has begun. And the Cenobites encourage you to finish it to claim your prize. Same mechanic, just delayed.

Arrogant assholes like Voight think the rules don’t apply to them. He attempts to get other people to take the hit for him so he can reap the rewards. But the house always wins in the end.

The Lore and Laudarant Configurations seem to have gone without much explanation, besides your own interpretations. Can you give us an official answer to what these could offer the solver?

Luke Piotrowski: We had to leave something for a potential sequel! I can’t give an official answer. Nothing’s canon until it’s canon. On screen or in an official novel, comic, etc.

But as the guy that came up with them… Lore is knowledge, Laudarant is love. Similar to Liminal, I suspect Lore would give you what you desired… in horrific abundance. What was that old Upright Citizens Brigade sketch? The bucket of truth? Imagine having all of the knowledge of the cosmos beamed into your mind. A Lovecraftian sort of glimpse of the other side, the scope of eternity. It would mentally obliterate you. I suspect it would be something along those lines.

As for Laudarant… same rules apply. What does way too much love look like? I’ll leave that to everyone’s imagination but whatever it is, it isn’t pretty.

What was the hardest scene to write (or re-write) – perhaps one that changed dramatically from what you first imagined to what ended up on screen?

Luke Piotrowski: Ah, the scene with Menaker in the hospital with Riley was written so many damn times. Menaker was a man in the early drafts which gave it a very different flavor. That was another big exposition scene that kept being written and rewritten. For a number of reasons, I think it ended up being the weakest scene in the movie. We didn’t have a ton to work with and had to piece a lot together in the edit.

Ben Collins: The Trevor scenes stood out to me because the character was both fundamentally deceptive, but also one of the main voices of covert exposition throughout the film. So it was hard to find a “character” on the page that felt like a person, as opposed to a device that serviced the plot. So all of Trevor’s dialogue was being rewritten throughout the development process and it wasn’t until we had Drew Starkey cast in the role that David Bruckner felt he could get a handle on how to imagine the Trevor character. So many of the key scenes with Drew were rewritten during production to fit to Drew’s presence and affect and he became a three-dimensional character in a way that he never was on the page.

Did budget, production realities, or studio feedback force you to cut or change any of your favourite ideas? Which ones were sacrificed, and which ones got improved because of constraints?

Luke Piotrowski: I’ve alluded to a few things. I had some Cenobite origin ideas I wanted to hint at. And the quadrupedal form of the Weeper would have been so fucking cool. Voight’s sex dungeon ultimately felt a bit smaller and tamer than I would have liked.

Other than that… the scene with Colin almost being claimed by the Gasp in the end was staged in a swimming pool originally. I loved the idea of seeing the chains grab him underwater. Keeping him inches from the surface, fighting for breath. And that meant they dragged Trevor down into the water too. Highlighting even more his descent and Voight’s simultaneous “ascension.” I’m a big fan of baptism imagery.

Oh, and one other image I adored and kept trying to incorporate was our Pinhead’s jewelled pins being able to sink into and emerge from her head. Sort of like the plumage of a bird. Something that felt organic. Like goosebumps. The way the body responds to sexual stimuli, I wanted to see them emerge when she first appeared or sink into her skull, penetrating her brain when she gives Voight his “exchange.”

With Voight becoming a Cenobite at the end, is this for Leviathan’s own personal agenda, or will Voight be joining the ranks of Pinhead and the ‘Gash’?

Luke Piotrowski: My assumption was that he would be joining their ranks. In my mind, the original Cenobites are truly divine but their ranks have been swelled over the years by humans who have solved the box, made their sacrifices and chose Power. What truly gets Voight off is not sensation but dominance. He wants to be the one holding the whip. He wants to be a Cenobite.

Ben Collins: In Hellbound: Hellraiser II there’s the whole sequence where they reveal the previous human life of each of the Cenobites and as interesting as some of it is, I was personally never satisfied with that explanation of their origins. So I think we wanted to show that Voight was exceptional in some ways, his dedication and persistence made him eligible for the ultimate gift Leviathan has to offer, but not necessarily suggest that the same is true of each of the Cenobites we see in the movie.

That way there’s always more mythology to unpack in future films.

If given the chance to continue, what aspects of the mythology would you most want to explore in future installments?

Luke Piotrowski: I love Hellbound so much. I’d love to see more of the labyrinth. But I also love the comics and how they would tackle different types of stories and different time periods. I’d love to have the time to maybe build out an ensemble cast of characters.

Whatever it was, I would like to take inspiration from Clive Barker’s stories. The mythology is only as interesting as the characters confronting it. So something a bit more overtly sexy and overtly queer and overtly fucked up would be fun.

Are there elements or characters you would like to explore in sequels or spin-offs? If the movie leads to further installments, what threads do you feel most excited by to explore?

Luke Piotrowski: I think I’d want to close the door on Riley’s story and introduce someone new with a new set of demons and desires to explore via the box. Outside of digging into the quasi-biblical origins of the Cenobites I am intrigued by Lemarchand. All the Euro-Carnivale aspects of Bloodline. I would be interested in maybe following someone into the sinister occult underworld of France or something. Get some of the globetrotting flavor the opening of the original film has.

Ben Collins: One of our goals with the one movie was to hopefully build a functional engine for future instalments, whether we were involved or not. The creation of the multiple configurations and the process one has to go through in order to reach a reward is story mechanism that could interact with characters and plots.

What do you see as the future of the franchise? Is a sequel something you’d like to be part of, or do you both know anything that you can share? Keith Levine went on record early last year to state that talks are happening.

Luke Piotrowski: Ben and I are writing separately now but I think a Hellraiser sequel is something we would both eagerly team back up for. I wish we had more concrete news to report. Tell Hulu, keep streaming it! That’s the only path forward that I can see.

Obviously, we’re all excited about the prospect of the video game. And I’ve started to explore writing comics. I’d love to see the comics make a comeback and be a part of that.

Ben Collins: Luke and I have always believed that the world Clive created could support any number of interesting stories and that we’d love to have another chance to find one. We’ve all been very busy with different projects since we finished Hellraiser in 2022, but if the right opportunity presented itself we’d be honored to come back.

What are your thoughts on the upcoming Hellraiser video game, Revival, and how the mythos might work being translated into a game? Will you both be playing it?

Luke Piotrowski: I’ve seen the trailer but not much beyond that. I’m excited to see it expand on the aesthetic of the original films. I’ll definitely check it out. I love survival horror games. I’m sure everyone can spy a little Silent Hill DNA in Hellraiser 2022. Anything that keeps the franchise alive and growing is a good thing in my book. Let there not be a generation who doesn’t know who Pinhead is!

Ben Collins: I’m very curious to see how it works! I definitely think some things can translate better to games than they do as movies, but I don’t know that I ever considered whether Hellraiser would fully work in that medium so I’m interested to check it out.

It’s probably worth mentioning that Martin Emborg, the designer who made the configurations in our movie also made a Hellraiser inspired game called Echo that is available on Steam. Unfortunately it’s only on PC so I’ve never played it but I hear it’s cool and that’s how we initially became aware of his work.

What can fans hope and expect to see from yourselves in the future? Any exciting upcoming projects for you both?

Ben Collins: I’ve been writing a lot of new stuff but the one I’m most pumped about right now is a psychological thriller I wrote called No Smoking, No Pets. It’s an original screenplay and I’ve reunited with the team at Phantom 4 (David Goyer, Keith Levine, Gracie Wheelan, and David Tracy) to produce. I can’t say too much but hopefully more will be announced soon. Thank you guys for being interested enough in wanting to hear what we have to say about this movie! I hope we answered everything satisfactorily enough!

Luke Piotrowski: We actually just had a new movie hit theaters this year, a crime thriller called She Rides Shotgun starring Taron Egerton, based on the novel by Jordan Harper. It’s available on VOD now. Super propulsive and intense with a big heart. It’s about an ex-con forced to go on the run with the ten year old daughter he’s never had the chance to know. I’ve also got a couple big solo projects I’m working on that haven’t been announced yet. One of which is another very different but very exciting horror remake. The other is an adaptation of a recent horror novel. I’ve also got an original film I’m hoping to direct. We’ll see what happens there. But I definitely have my first comic book, Ferocious, coming out from Mad Cave Studios this fall. Six issues dropping monthly starting in November. It’s a heartfelt, violent twist on the classic revenge story set in a dark fantasy world. A little Berserk, a little Lone Wolf and Cub. I’d love people to check it out.

----

Many thanks to Tony Searle of the Hellraiser Discord Community for providing us access to this intriguing discussion with Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski! To read the full interview with Ben and Luke, as well as other interviews from key figures in Hellraiser history, be sure to visit and join the Hellraiser: Revival Discord page and check out their YouTube channel: