“In Haiti, there are secrets we keep, even from ourselves.” Throughout his career, Wes Craven was a filmmaker who provided countless nightmares and celluloid terrors, but there was one film that managed to haunt me in such a manner that it left numerous scars on my young psyche, and that was The Serpent and the Rainbow. Adapted from Wade Davis’ book of the same name that provided a clinical examination of Haitian voodoo, zombification, and the power of tetrodotoxin—a powerful hallucinogenic—Craven’s powerful descent into the real-life madness of Davis’ experiences is easily one of his most ambitious, and quite possibly the Master of Horror’s most introspective, efforts from his entire filmography.

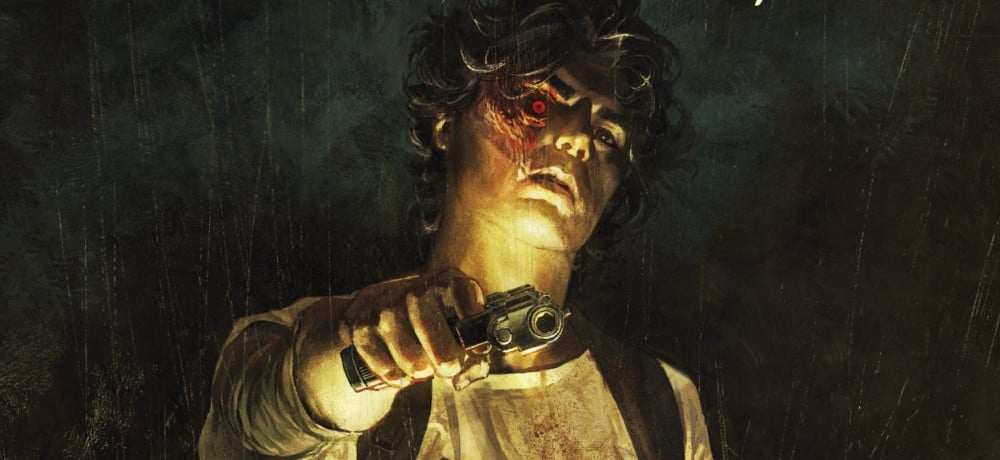

In The Serpent and the Rainbow, we’re introduced to anthropologist Dr. Dennis Alan (Bill Pullman), who spends his time in remote corners of the world studying rare plants and herbs that could potentially have medicinal uses amongst the pharmaceutical community here in the States. His latest assignment takes him to Haiti, a country on the verge of a political revolution, where the good doctor is tasked with retrieving a poison that can apparently turn victims into zombies, in hopes that the drug may have practical applications for patients undergoing surgery who have adverse reactions to general anesthetics. But the more Dennis chases after the “zombie drug,” with the help of Dr. Marielle Duchamp (Cathy Tyson), the deeper he finds himself plunging into a literal hell, as Captain Dargent Peytraud (Zakes Mokae), commander of the Tonton Macoute paramilitary force, has set his sights on torturing the doctor, both physically and mentally, and will stop at nothing to ensure that the pesky American stays out of his way.

There’s no denying that when it came to many of his films, Craven was probably the horror genre’s greatest metaphysical explorer, someone who was very driven by investigating ideas that feel very real, yet extend far beyond our reality. Things like the power of dreams, the existence of the human soul, the concept of faith, and whether or not there are forces of magic at work in this world are concepts Craven have explored in a variety of his works, but in The Serpent and the Rainbow, we watch as all those themes collide with the very real-life horrors of Haiti and the political corruption that has ravaged its residents. Social warfare is being waged everywhere in Haiti, and once Dr. Alan arrives in the country, he also finds himself in the cross-fire of the turmoil, but he has bigger problems as the battle for his soul is being relentlessly waged within the confines in his mind, courtesy of Captain Peytraud.

And that’s the key to what makes The Serpent and the Rainbow so compelling: having an actor like Bill Pullman as Dr. Dennis Alan, who can pull off haughtiness and vulnerability equally with the greatest of ease. There’s a quiet overconfidence to his performance in the film. Dennis' arrogance usually ends up being his downfall in various scenes, and his Harvard education means absolutely nothing because he’s ill-prepared to contend with the mystical forces at work, ones that he has no real comprehension of until Serpent’s reality-bending finale where it all finally clicks for him. There’s a swagger to how Pullman carries Dr. Alan throughout the first half of The Serpent and the Rainbow (maybe from his work in Spaceballs?), but the more that Captain Peytraud chips away at his consciousness, you should keep an eye on Pullman’s physical carriage in the film—even the way he walks or hangs his head changes completely (and this is before the infamous nail-in-the-scrotum scene). I would imagine this was also Craven’s way of exploring the idea of how Americans often view the rest of the world with an unearned sense of superiority, and we see what can happen when our ego gets us into a kind of trouble that we cannot begin to comprehend.

Another interesting touch to The Serpent and the Rainbow is how often Dr. Alan is oblivious to the omens of danger around him. Because he’s so urgently compelled by his sense of discovery (which is certainly ego-driven at most times), and even though he receives numerous warnings—both in real-life and in his dreams—Dennis’ determined sense of purpose in The Serpent and the Rainbow never wavers. Whether it’s the “zombie drug” that could potentially change the face of modern medicine, or the well-being of Dr. Duchamp after he’s returned to the States, Pullman’s character remains fiercely focused, with little consideration of his own well-being.

Dr. Alan’s single-minded sense of purpose ends up irking the corrupt Captain Peytraud, a man who utilizes his political influence, as well as his penchant for barbaric torture, just as easily as he wields his dark influences over everyone. We get an initial inkling of the kind of power Peytraud is capable of very early on during a scene at Lucien Celine’s (played by the always excellent Paul Winfield) night club, where a simple clinking of a glass sends a dancer off into a murderous tizzy. The more time Dennis spends in Haiti, the more we see the type of depravity Peytraud is capable of, in both a real-world sense as well as on a spiritual level, making him easily one of the most terrifying characters Craven has ever brought to the big screen.

Of course, the reason Captain Peytraud is such a dominant villain in The Serpent and the Rainbow is due to Mokae’s chilling performance as a man who can curdle your blood just as easily as he can charm the pants off you with his enigmatic presence and acute ability to turn a phrase or two. Another intriguing aspect to Peytraud is that he is someone who can torment his victims in a variety of ways (similar to how Craven used the character of Freddy Kreuger in both the original Nightmare on Elm Street and New Nightmare, or even with Horace Pinker in Shocker later on), where he’s not just a threat in reality, but he’s also someone who is going to screw with your self-awareness on a totally different plane, often driving victims to madness before stealing their lives and their souls. He such a dangerous entity in so many ways, making him truly one of the most fascinating villains of the horror genre, in the year 1988 or otherwise.

Another thing that makes Peytraud an interesting antagonist in Serpent is that if you really look at it, he’s not an unreasonable man (albeit, he is still a sociopath). He gives Dennis numerous opportunities to go back home without so much as leaving a single scratch on the determined anthropologist. But once Dr. Alan performs the rituals to concoct the mystifying potion that can seemingly turn those afflicted by its poisons into the walking dead, that’s when Mokae’s character amps up his response to what he perceives as Dennis’ total insolence and disrespect for his authority over the Haitians.

Which brings us to the aforementioned nail-in-the-naughty-bits scene.

There are a number of things from The Serpent and the Rainbow that will stick with you, because Craven was always a master of creating hauntingly iconic imagery in his movies, but seeing Pullman strapped down naked to a chair, with Mokae holding a disturbingly sturdy-looking hammer and a nail that appears to be bigger than my entire head over Dr. Alan’s genitals, ranks right up there as one of the most horrifically haunting scenes Craven ever dared to direct throughout the 1980s. It’s such a savage, yet simple, moment of vulnerability and brutality that has become one earmark of just why The Serpent and the Rainbow has been able to stand the test of time. When Peytraud barks at Dennis, “I want to hear you scream,” we all feel that moment, regardless of whether or not you have testicles.

Another hallmark sequence in The Serpent and the Rainbow is Dr. Alan’s nightmare of being buried alive by Captain Peytraud, ending with him being submerged in a coffin filled with blood, screaming in absolute terror. Of course, there’s also the scene where Pullman’s character actually gets buried by Peytraud (along with a tarantula—DEAR GOD), and Craven fully immerses us in the horror of not only what it’s like to essentially live through your own “death,” but the sheer hopelessness and panic of being buried alive to boot. Tapping into this fear for the film’s tagline (Don’t bury me… I’m not dead!) was sheer brilliance, too.

As much as the film's effective scares are due to Craven’s creative sensibilities as a director aptly tuned in to what disturbs us as human beings, another driving force behind the striking visuals in Serpent is cinematographer John Lindley, who goes to great lengths to capture the frenetic energy of a country teetering on the edge of chaos, much like Dennis’ sanity in The Serpent and the Rainbow. Lindley also utilizes some nifty tricks of the trade to put audiences squarely in Pullman’s shoes (the coffin sequence and the scene when he’s poisoned and left for dead on the streets are two prime examples), and the results are both dizzying and unforgettably disturbing.

We’re told at one point in The Serpent and the Rainbow that Haiti is a country full of contradictions, and that is demonstrated through Lindley’s assured lens, which perfectly captures the juxtaposition of the simple beauty and wonders of Haiti as a locale, versus the political strife that has left the population ravaged on a socio-economic level. These are people living through complete political turmoil, and yet, their faith in their belief system still remains steadfast, something that we see demonstrated during the stunning pilgrimage scene where thousands of extras trek alongside Duchamp and Alan to a sacred waterfall whose waters have healing powers.

There’s an authenticity to Lindley’s footage in numerous scenes as well, including the coal and glass eaters (oh, and who can forget the guy who sticks needles through his face? Yikes!) at Lucien’s night club, who were actually under the hypnotic power of a voodoo trance during the filming sequence. Very few films have ever been able to capture real-life mysticism the way Serpent does, and that’s just another reason why this movie feels so unique and completely unlike anything else from Craven’s filmography (or even the horror genre as a whole).

At one point in The Serpent and the Rainbow, Dr. Duchamp remarks that “God is in our bodies, in our flesh,” which is an important moment in the script, because her character represents the intersection of faith and science, and how the two practices don’t always negate each other, which I think was one of the biggest ideas that Craven was exploring here. Tyson’s character is a medical professional who can clearly accept both the existence of otherworldly practices and rituals, but still has a practical sense about how these things can affect her work at the mental health facility she oversees. So many times in film, we see this struggle where a director is pitting religion versus practical knowledge, so it’s refreshing that here, Craven is looking to do something different, and is interested in pitting the two schools of thought against each other beyond just Dr. Alan’s own reservations.

Haitian voodoo is treated with great respect by Craven in The Serpent and the Rainbow, too, and as a storyteller, he never utilizes the religion as a punchline (there are no Weekend at Bernie’s II type of shenanigans here). In this film, voodoo is just as valid of a belief system as Christianity, Catholicism, or even the scientific method. There is a reverence shown, and it’s clear that Craven isn’t here to use voodoo to illicit thrills and chills; he’s genuinely digging into what happens to the human soul after death, and whether or not there are supernatural forces at play in this world that go beyond what most of us could possibly comprehend.

We’ve seen it time and time again where strange rituals, through the lens of the “outsider,” are viewed as these crackpot practices, but in the sequence when the vivacious showman Louis Mozart (Brent Jennings) concocts the infamous zombie drug, the entire process is a time-consuming journey filled with haunting and enchanting rituals, and also closely follows Davis’ description of the methodology in his book. Craven isn’t here to pass judgment in The Serpent and the Rainbow; he’s here to explore all possibilities, and I suspect that filmmaking was his way of investigating a variety of metaphysical concepts that drove the narrative of so many of his films.

As a whole, The Serpent and the Rainbow perfectly represents the type of filmmaker Craven was: a bold and fearless visionary with a wildly evocative imagination who was constantly searching for answers about the human condition through his craft. A man who consistently took risks throughout his entire career, The Serpent and the Rainbow represents some of the biggest gambles Craven ever took as a director, which says a lot when you examine his entire filmography, and that’s why the film is still just as powerful today as it was when it was first released in 1988. Perhaps Wes saw himself in Dr. Alan, and Serpent was his way of trying to examine his own fears about mortality and pinpoint whether or not there is more to life than just existing on a physical level.

---------

Be sure to check here all month long for more special features celebrating the Class of 1988!