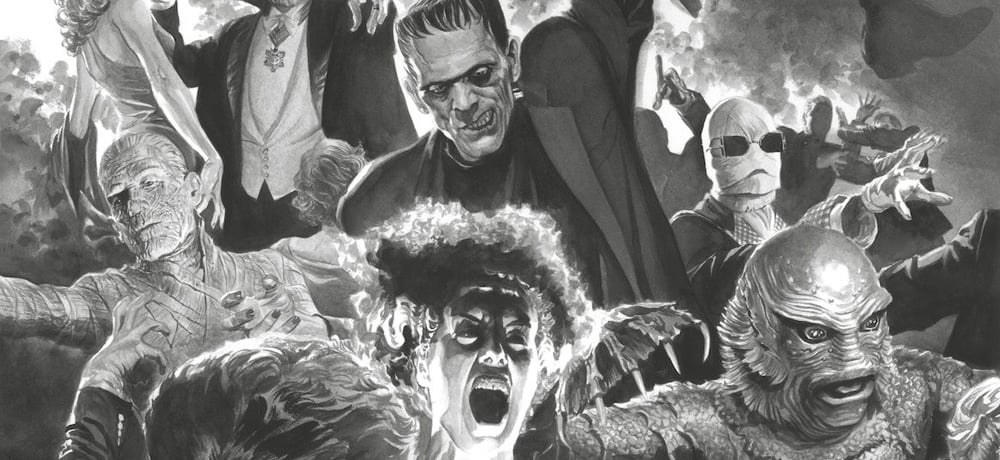

From 1925 to 1956, Universal Studios produced three dozen horror films, with monster characters that have become legendary: the Phantom of the Opera, Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, the Mummy, the Invisible Man, the Bride of Frankenstein, the Wolf Man, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon. Though terrifying to audiences at first, by the end of the cycle, these characters had become caricatures. First they played straight characters opposite Abbott and Costello’s hijinks, and then they were completely defanged to become the Munsters, silly sitcom versions of their former sinister selves.

And then, nothing. Sure, there have been various reboots and reimaginings. But flat-topped Frankenstein, Hungarian-accented Count Dracula, and all their brotherhood never appeared in their original forms again.

But just like in the movies, the monsters refuse to die.

Today, there is still a thriving subculture of Universal Monster fans. A new generation of monster-lovers has re-discovered these characters and kept their spirit alive.

I first encountered this community in a Facebook group, unaffiliated with Universal. I figured its members would mostly be film buffs, horror aficionados, cinema students, and, frankly, old folks. But according to one group administrator, 23% of the group is female and 25% is under the age of 45. And to prove the global popularity of these films, a quarter of the members were international, from as far away as Italy, Brazil, and Australia.

All the content of these groups comes from members, who produce an average of 45 posts a day. These include trivia, collectibles, behind-the-scenes photos, posters, amateur art, polls, and general musings. “Younger members are just discovering these films,” one group moderator tells me. And there are half a dozen major groups, along with smaller niche groups that focus only on collectibles or certain actors.

Where did this modern love come from? I wondered if it could be tracked to childhood. After all, since the films are no longer really frightening, they can be safely viewed by children. I myself remember first watching them as a kid with my movie-loving father. And the Universal Monsters have virtually defined Halloween; google “kids trick or treating” and you will almost always find a miniature version of Bela Lugosi’s Dracula or Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein’s Monster.

Darcy Marks is a monster fan from Vermont. She agrees the films no longer pack a horrifying punch, but views that as an advantage. “That's what made them so accessible as a kid, and because [of that], there's this huge sense of nostalgia that makes them still beloved.”

Marks has a tattoo of Bela Lugosi as Dracula. “I will never forget seeing his eyes in that way,” she tells me. “I was absolutely struck.” In fact, there are plenty of members sharing tattoos in the Facebook groups. This indicates not only the youth of these fans (the most-tattooed age group is 30–39, according to Statista), but also the intensity of their devotion.

I spoke to 35-year-old Callum Stewart, a resident of Scotland, whose leg features a tattoo of the Creature from the Black Lagoon. “He just looks so cool!” He told me. “Definitely the best-designed monster of his era.” But there was a deeper connection there: “I can sort of relate to him in that he’s just a dude who wants to live his life and be left alone, but these assholes won’t just let him be.” Stewart also feels a sense of community around the love for these characters, and his tattoo serves as a sort of secret handshake. “It's cool to get someone who knows [the Creature] and we can have a chat about monsters.”

Belonging to an online group is one thing; tattoos are another. I talked about this level of affection with fantasy writer Phil Athans, author of Writing Monsters, which breaks down what makes fictional creatures compelling. “One of the things Universal brings to the table is monsters that are uniquely humanized,” which matches Callum’s description of the Creature as “just a dude.” Though nowadays horror means films like The Witch and Midsommar, Athans says, “There’s still room for horror that feels more fun.” That’s where the Universal Monsters come in.

Still, they’re the bad guys. Why do we cheer for these gruesome creatures and not the Van Helsings who hunt them? “There is a transgressive thrill to switching teams—sometimes we are going for the heroes and heroines, but other times we’re finding real pleasure in what the monster does,” says Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, author of 1001 Women of Horror. “Lugosi and Karloff could at times be hugely sympathetic, so while we find them scary, we might equally feel pity or even empathy for them.”

Film historian Emma Westwood agrees, especially when it comes to Universal’s most famous female monster. “Women in these films are usually horrified witnesses to the folly of man. And, let's be honest, the Bride of Frankenstein is a horrified onlooker, too. She wakes up, rejects the arrogant presumption that she should be the monster's mate, and then she dies.”

Westwood also has a theory about the popularity of clothes, internet memes, and, yes, tattoos. “The imagery of these films is so breathtaking, which is probably why people are still drawn to their iconography. They fall into the category of classic masterworks.” She likens the Universal Monster images to Elvis or Marilyn Monroe, whose symbolism eventually transcended the actual person. This iconic status makes them perfect for today’s world of visual shorthand—and for visual platforms like Facebook.

Few people alive today have a better view of monster fandom than Antonia Carlotta. She’s the great-grandniece of Universal founder Carl Laemmle and hosts a YouTube channel about the studio’s history. She agrees that age is no barrier to loving these characters. “When I first got into the Monsters, I often found I was the youngest person in the room, so it’s incredible these days to see a generation younger than me getting involved.” She interacts with fans on YouTube, Facebook, and message boards. “It really starts to feel like a giant family. All of these people who share a passion and are just so excited to share stories from the past, or different ways the Monsters are a part of their lives in the present.”

Her great-aunt, Carla Laemmle, had small roles in the silent Phantom of the Opera and Dracula (in which she spoke the opening lines). Though she was no horror star, “she received letters every single week,” Carlotta says. “I used to go to conventions with her, and it was incredible to see how many fans she met at every one.” Monster buffs sought out any connection they could find.

She and Westwood provide a final theory on why the Monsters’ popularity endures: They’re all social misfits. They’re misunderstood and unfairly victimized. Virtually everyone can relate to that feeling of alienation—particularly young people, as they struggle to find their identity and place in the world. “Frankenstein’s Monster is the ultimate outsider—the most punished of pariahs—the embodiment of the ills suffered by any marginalized group,” says Westwood.

Antonia agrees: “I think a lot of people see themselves in the monsters, whether that’s feeling like an outsider, or trying to make sense of the world in some way, or wanting love, or wanting power.”

As long as these human desires and human fears exist, people will find kinship in these inhuman characters.

[Image Credit: Above image by Alex Ross.]