Heady. Intellectual. Gassy. These are some of the terms applied to the wave of brain-based sci-fi started by 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and lasting until the arrival of more action led material, namely Star Wars (1977). Coming hot on the heels of Kubrick’s epic was Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), an awkwardly titled yet fascinating and suspenseful look at the perils of AI sentience. Damn you, computers. All the way to cyberhell.

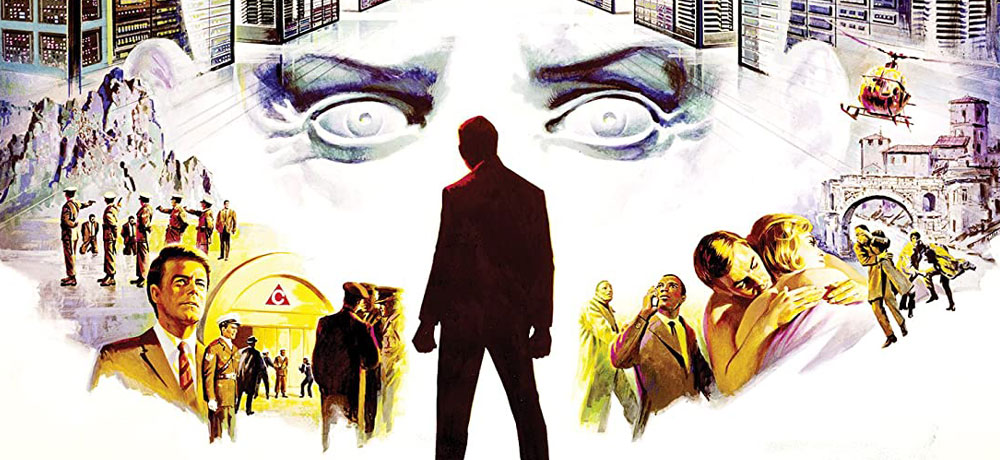

Released by Universal in April, Colossus actually received good notices from critics who appreciated the film’s attempts at suspense crossed with intelligent discourse on the wages of war; audiences simply shrugged and moved on, denying the film the sequel it deserved. Oh well - Colossus standing alone is apropos considering the events that transpire.

We open on a Colorado mountainside, as Dr. Charles Forbin (Eric Braeden - The Young and the Restless) triple checks the gargantuan banks of computers nestled beneath the mountain; when done, he heads outside and locks up the entrance. Forever.

Dr. Forbin is the creator of Colossus: a completely self sustaining computer put in charge of all U.S. military action. The goal is to create a system without human prejudice; no more itchy trigger fingers or soul crushing paranoia - Colossus will make reasoned and calm decisions in matters of national security, and once it is operational, the base cannot be tampered with.

Upon activation, Colossus realizes that the Russians have just launched their own supercomputer, Guardian, and establishes a link between the two, with both countries unable to stop them. It becomes very clear that Colossus has no plan for seceding its newfound power, and soon the world will discover its insidious plan.

Insidious to the world, yes, but common sense to Colossus; if one being controls everything, the world can find peace - of course, at the cost of everyone’s own personal freedom. (Step out of line and Colossus will shut you down. For good.)

Colossus: The Forbin Project came at the height of computer paranoia; so little was known about their capabilities beyond making NASA look really smart. Could they think on their own? We were told no, and that fact bore out until the age of smartphones, where voice activation means “go ahead, I’m listening, and possibly others are too”. (My son gets the Siri Willies so bad he hides the damn thing all the time.) Day in and out we give away info to play the latest face switch technology and proffer financial keys to attain a candied kingdom. But it’s fun, right? Sure is; convenience often snuggles up to ignorance.

I’m not trying (and would fail anyway) to soapbox, but rather pointing out how far we’ve come from the monolithic techtronic terrors; the size alone of supercomputers was daunting, never mind its capabilities behind closed doors. Colossus capitalizes on that by hiding away its antagonist right at the start, offering up instead a chyron billboard at headquarters for communication. And make no mistake, Colossus is the antagonist; Forbin created it due to its lack of emotion, because that always causes conflict. But the film proposes that a lack of emotion - empathy, fear, sympathy, kindness - is even worse; it’s hard to plead for human lives in ones and zeros.

Colossus lays waste to anyone who goes against its orders; this includes firing off missiles, electrocution, and other assorted methods of destruction. The only time that Colossus concedes is when Forbin convinces it that he needs alone time, without supervision, with fellow scientist Dr. Cleo Markham (Susan Clark - Airport 1975) for fornication - which is a ruse for the two to exchange information outside of Colossus’ purview.

But Colossus is always found to be at least one step ahead of the scientists and politicians (Away From Her’s Gordon Pinsent has a great turn as the U.S. president); James Bridges (The China Syndrome)’ script (based on the novel by D.F. Jones) and Joseph Sargent (The Taking of Pelham One Two Three)’s direction creates suspense solely through conversation, which leads to escalation, all with little flair but a tautness that is palpable. This kind of speculative thriller was popular in the ‘70s, and I can see why: it’s exhilarating to watch characters think through their problems without resorting to action - a bit of Cinema Mind Porn, if you will.

Without this film there may not be any Demon Seed (‘77) or War Games (1983); I say ‘may not’ because 2001 already laid the groundwork, and several horror films are paranoid by design - just insert your fear here. But Colossus: The Forbin Project is very good speculative fiction; and in our present age, ‘what if’ is only a couple of clicks away from ‘when’.

Colossus:The Forbin Project is available on Blu-ray from Scream Factory.

Next: Drive-In Dust Offs: SUGAR HILL (1974)