It’s hard to believe that prior to the mid-’80s when Frank Miller (Sin City, Daredevil, 300), got his evil genius hands on the Dark Knight with the landmark graphic novel, The Dark Knight Returns, the figure of Batman was defined by the kitschy ’60s TV show starring Adam West and the bright and sunny pages of Bob Kane’s original Detective Comics. Released in 1986, The Dark Knight Returns cast Batman as a moody, bitter, aging caped crusader: a musclebound vigilante who spends his nights crashing a tank (Miller’s unique spin on the “Batmobile,” which had a lasting impact) through the grimy streets of a Gotham that closely resembled the rain-soaked, gothic aesthetic of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982).

From this point on in comics, television, cinema, and the general public consciousness, Batman was forever reinvented as a brooding, tragic, gothic figure who often occupied the thin line between hero and anti-hero. When Tim Burton was handed the reins for Batman’s first real foray into cinema, the director’s pop-goth aesthetic fit perfectly in line with the character that Frank Miller and others, such as Alan Moore (The Killing Joke) and Grant Morrison (Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth), had molded in the preceding years. Burton’s sequel, Batman Returns (1992), was even darker, pushing the director’s penchant for whimsical, gothic environments and storytelling even further.

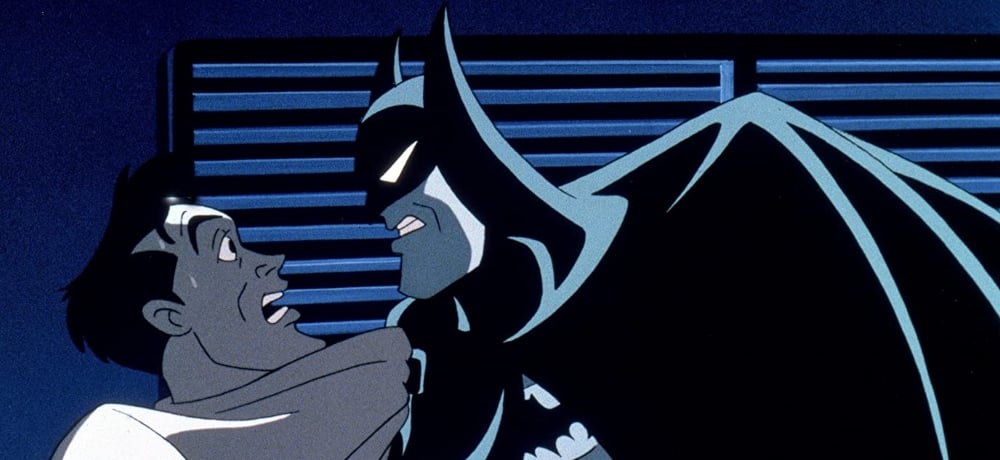

In 1992, the gothic minimalism of the most influential Batman comics and the dramatic flair of Burton’s films were married for what is considered amongst numerous fans (myself included) to be the finest screen adaptation of the character to this day: Batman: The Animated Series, created by Eric Radomski and Bruce Timm. Running from 1992 to 1995, with episodes produced, written, and directed by some of the most capable minds in animated series history, including Boyd Kirkland, Paul Dini, Kevin Altieri, and Frank Paur, all of whom also contributed their writing chops to other quintessential animated series such as X-Men: Evolution (2000–2003) and Batman Beyond (1999–2001, the futuristic cyberpunk successor to BtAS which, in many ways, rivals its predecessor with equally adept storytelling).

In the world of BtAS, Bruce Wayne (voiced superbly by Kevin Conroy) was beautifully translated as the tortured victim of circumstance found in the comics, giving viewers a deeper insight into the character’s melancholy than ever before. In addition, the gothic noir art style which came to define Radomski and Timm’s Gotham City was dubbed the “Dark Deco” aesthetic by the creators. The monstrous backdrops, composed of twisted, Calgari-esque skyscrapers and a blood-red sky, gave the show a moody, and at times, genuinely hellish veneer.

Also improved and fleshed out from their comic book counterparts were the members of Batman’s considerable rogues’ gallery. Mark Hamill’s Joker, with his effortless transition between sardonic quips and terrifying menace, became the voice every ’90s child would hear in their heads when reading Joker-related content going forward. Indeed, as much as I appreciate Jack Nicholson’s, Heath Ledger’s, and Joaquin Phoenix’s varied cinematic takes on the character, it is my opinion (and the opinion of many fellow Dark Knight fans) that Hamill’s Joker is the definitive interpretation of the Clown Prince of Crime. Simultaneously, Two-Face was given a major reconstruction in the brilliant two-part introductory episode detailing his origin story as a tragic victim of mental illness and the mob. Penguin’s look was similar to Danny DeVito’s in Batman Returns, while his voice was given sophistication by the silky smooth tone of Paul Williams (whom horror fans should recognize as the devilish record producer Swan from Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise). Batman’s more overtly grotesque foes, such as Killer Croc, Bane, Man-Bat, and Clayface (voiced by character actor Ron Perlman) were also remarkably handled in episodes which drew fruitfully from monster movie history and the work of H.P. Lovecraft. By the same token, Poison Ivy and Catwoman (voiced by legendary scream queen Adrienne Barbeau) were turned into sultry femme fatales, the show’s strong writing ensuring that they were as formidable as any of their villainous male counterparts.

One of the most disturbing episodes of BtAS is, in fact, one which involves Poison Ivy. In a plot that would make David Cronenberg proud, "House and Garden" (Season 2, episode 6) follows a supposedly reformed Poison Ivy as she creates her own inhuman “family” a la Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) from living plant matter. Another of my personal favorites is the episode "Dreams in Darkness" (Season 1, episode 31), in which Batman, under the influence of the Scarecrow’s fear toxin, is placed in Arkham Asylum amongst the very criminals he’s worked so diligently to keep locked away. The impressive narrative quality of Batman: The Animated Series wasn’t lost on television critics either, and the show was awarded numerous Emmy Awards during its run.

With the series’ penchant for the gothic and the macabre firmly established, it’s no surprise that the darker elements which make Batman such a strong and fascinating character were pushed even further with Radomski and Timm’s full-length animated “tie-in” movie, Batman: Mask of the Phantasm (1993). To put it concisely, the film is a visual masterpiece—one of the greatest animated films ever made, particularly of the comic book variety. Phantasm’s narrative is derived from the best elements of gothic literature and noir storytelling, incorporating psychological horror and genuine mystery into a piece that, despite its PG rating, is anything but child’s fare.

The story hops between the past and present, as a new threat arrives in Gotham in the form of the mysterious and ghoulish “Phantasm” (a moniker which could only be an ode to Don Coscarelli’s cult horror masterpiece of the same name). Dressed in a ghastly specter disguise resembling a cross between Michael Myers and guitarist Mick Thomson of Slipknot, wielding an arm-mounted scythe, and able to disappear at will amidst a cloud of smoke, the Phantasm holds a lethal grudge against several prominent figures in Gotham’s underworld, seeking them out and dispatching them like a murderous version of Dickens’ Ghost of Christmas Future.

The most remarkable instance of the Phantasm’s wrath occurs in a cemetery (at least a third of Mask of the Phantasm takes place in cemeteries, leaving no doubt as to Radomski and Timm’s gothic preoccupations in the telling of this story), where he frightens mob boss Buzz Bronski into an empty grave. Bronski doesn’t last long; he’s swiftly crushed to death under a falling headstone. It’s a scene straight out of a Mario Bava film, and one that I venture to guess would be far from acceptable in today’s PG-rated fare.

Meanwhile, Andrea Beaumont (voiced by Dana Delany), an old flame from Bruce Wayne’s past, reappears at a cocktail party, flooding Bruce’s mind with memories of his past prior to the emergence of the Batman. Andrea, a beautiful martial arts expert with a sharp intellect, was the daughter of a Gotham businessman in deep with the mob when Wayne was a young man. Meeting in a cemetery (of course, the premier location of the most decadent gothic romances) as they both pay tribute to their deceased parents, Bruce and Andrea fall head over heels for one another. A renewed hope for a happier and more comfortable life even puts Bruce’s plans for a life of vigilantism on hold. That is, until Andrea gives him a “Dear John” letter as she flees Gotham with her father to escape the mob. Bruce, of course, is heartbroken, and much to the dismay of his faithful butler Alfred, resigns himself to a life of crimefighting as Batman. These flashback scenes, I should add, are veritable masterclasses in accomplished, genuinely affecting storytelling. There’s a moment when Bruce returns to the cemetery in the midst of a storm, kneels before his parents’ grave, and begs them to forgive him for considering a life with Andrea. “It just… doesn’t hurt so much anymore,” he pleads. In another, Alfred looks on with noticeable anguish as Bruce reads Andrea’s “Dear John” letter and a colony of bats roar up from within the ground (revealing the future location of the Batcave beneath Wayne Manor).

As the narrative shifts back to the present, the missing pieces of Andrea’s sordid past are revealed to Bruce, and the remaining mobsters on the Phantasm’s kill list seek help from the Joker (another glorious Mark Hamill performance), the only individual they believe capable of stopping Batman, who they are convinced is responsible for the murders. The film culminates in a scene recalling many of the best Batman tales: a climactic battle between the Dark Knight and the Joker in which the identity of the “Phantasm” is revealed, as well as their connection to Bruce and Andrea’s broken past.

Mask of the Phantasm is a culmination of all the things that have come to define the Batman aesthetic: noir storytelling, brooding romanticism, elements of psychological horror, and gothic locales. And while ardent Batman followers shouldn’t have too much trouble deciphering the mystery of the “Phantasm” before the credits roll, the film does succeed in setting up a genuinely engaging and effective mystery which seamlessly encompasses the Dark Knight’s past and present. As a film that draws influence from and pays tribute to the horror genre in numerous respects, there’s something for every type of genre fan to relish here. Slasher and Giallo enthusiasts should enjoy the mystery surrounding the identity of the ghostly killer, while followers of gothic poeticism and old-school horror will find themselves transfixed by the film’s elements of doomed romance and funereal locales of cemeteries, cathedrals, and the stately, cliffside majesty of lonely Wayne Manor.

Whether or not one chooses to refer to him as a “superhero,” Batman has always been a tragic figure, one whose brooding sensibilities closely recall one of Edgar Allan Poe or Nathaniel Hawthorne’s doomed protagonists in stark contrast to the bright, idealistic wholesomeness of a character like Superman or Spider-Man. And Phantasm embodies this with aplomb. In my view, it is the greatest filmic translation of Batman yet conceived, despite the iconic live-action interpretations of Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan (and yes, the Joel Schumacher entries have their place as well, ideally after a few drinks). In a mere 76 minutes, Radomski and Timm deliver a phenomenal and lasting Batman narrative that, like no other film before or after, leaves its audience with a deeper understanding of Bruce Wayne’s tortured psyche and the rage, pain, and sorrow which drives him to go out night after night, seeking out criminals to terrify and punish.

With the impact of Covid-19 in pushing back so many anticipated theatrical releases, whether or not the upcoming Robert Pattinson vehicle The Batman (now scheduled for a March 2022 release) will honor the Dark Knight’s brooding legacy or simply become a blip on the radar (see Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice) remains to be seen. But, if it contains any of the elements that make Mask of the Phantasm such a lasting and resounding success within the Batman canon, then Pattinson and the filmmakers should consider themselves very lucky indeed.