Horror cinema, by nature, is most often concerned with the uncanny. The fantastic. The grotesque. Despite the genre’s largely fictional preoccupations, however, the macabre has always been a viable outlet for political and social commentary. In fact, the American horror film provides an often reliable indicator as to which forms of societal unrest plague the nation at any given time. Perhaps more than any other filmic genre, horror has provided an outlet for filmmakers to document government fallacy and real- life atrocity through the filter of fantastic, often supernatural, narratives. By hyperbolizing societal conflicts like war, civil unrest, poverty, and corruption, a good political horror film seeks not only to draw attention to such issues, but also to make them seem manageable by comparison. Take, for example, the premise of George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978). While Americans needn’t worry themselves over hordes of zombies rising from the grave to devour human flesh, the societal problem that Romero’s zombies symbolically embody—unchecked American consumerism—is a very real one. In the spirit of a tempestuous four years in American politics, and an even more contentious election cycle, let’s take a look back at the horror genre’s relationship with politics over the years...

From the genre’s inception in the 1930s (horror films, of course, existed in the silent era as well, but were not labeled as such), even the earliest American horror films touched on the nation’s concurrent political and social climate. Before the implementation of the puritanical Hays Code, the Universal Monster films that dominated American horror leaned towards escapism and the desire to temporarily forget the crippling anxieties brought on by the Great Depression and post-World War I society. The fantastical stories and clear-cut battles between good and evil exemplified in Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931), James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), and Karl Freund’s The Mummy (1932) provided audiences with much-needed relief from the fears of their daily lives whilst reassuring them that good would indeed triumph over evil as Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan) triumphs over Dracula (Bela Lugosi), and that life would, eventually, start to look up.

In the 1940s, during the height of World War II, American horror shifted away from vampires and gothic castles in favor of more minimalist, suggestive atmospheres. The films of Jacques Tourneur and Val Lewton, such as Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943), are prime examples. Perhaps the American horror film which best reflects the nihilism and existential despair of the 1940s (a decade defined by the horrors of the Holocaust, war, and massive loss of human life around the world) is the Val Lewton-produced 1943 film The Seventh Victim, starring Jean Brooks as Jacqueline, a lonely, death-obsessed woman who falls afoul of an evil cult. While Jacqueline’s sister, Mary (played by Kim Hunter), makes all attempts to save her, Jacqueline’s emotional resignation and eager preparation for the kiss of death ultimately seal her fate by the film’s conclusion.

It was during the 1950s that American horror began to more directly reflect the country’s cultural fears and role on the world stage. Following the decision of the Truman administration to force Japan’s surrender during WWII by using nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the American horror film found itself being defined by the Age of sci-fi horror. While Japan itself would reflect upon such wartime atrocity in their own horror cinema (see 1954’s Godzilla), America also sought to exorcise anxieties about the rising threat of nuclear power in giant monster movies such as Them! (1954) and Tarantula! (1955). In such sensationally titled films, insects and similar tiny creatures are mutated to gigantic proportions as a result of a nuclear energy disaster or some kind of science experiment gone awry. Happening simultaneously were the shameful allegations against American citizens by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the ensuing panic of communist infiltrators invading America. Thus, the stage was set for such quintessential ’50s horror films such as The Thing from Another World (1951) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). In both films, the extraterrestrial horror threat disguises itself under a veil of humanity, only to strike upon having successfully infiltrated American society.

Emboldened by the looming unrest growing beneath the tranquil veneer of ’50s America as well as the decline of the Hays Code, American horror films of the ’60s became rougher, tougher, and more true to reality. With the release of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), horror was no longer limited to the crypts and castles of the ’30s, the shadowy mise-en-scène of the ’40s, or the aliens and giant bugs of the ’50s. Instead, Psycho brought terror into the heart of America, suggesting that even the calm, genial boy next door could just as easily be a murdering psychopath. After Psycho, nothing was off limits in the horror film. All bets were off. The viscerally kitschy efforts of “Godfather of Gore” Herschell Gordon Lewis that followed, such as Blood Feast (1963) and Two Thousand Maniacs (1964), with their scenes of mutilation and bodily dismemberment, were additional reinforcement that the genre was steadily pushing the definition of “socially acceptable” filmmaking.

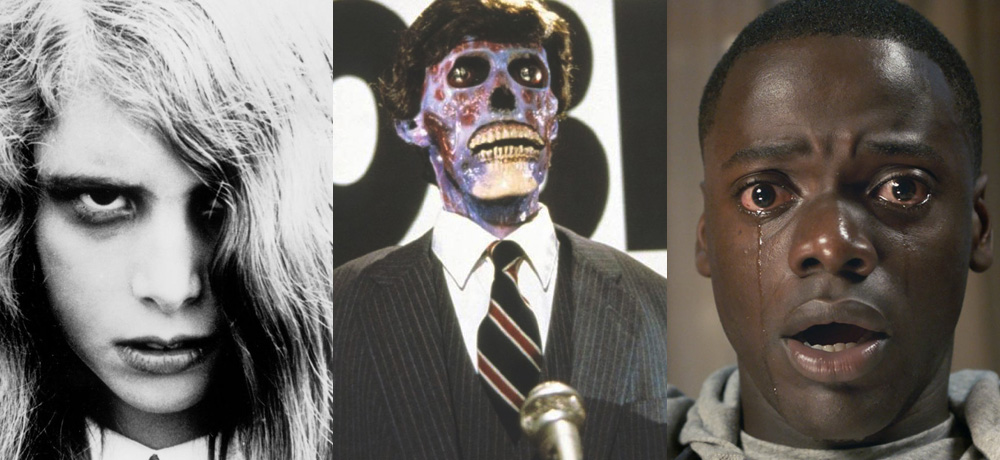

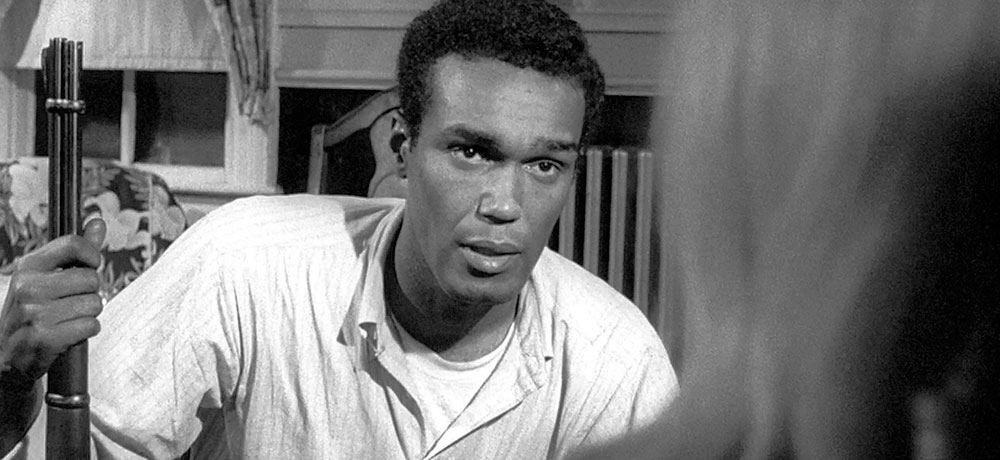

In 1968, the American horror film would radically reinvent itself once again, this time as a grimmer, more nihilistic, and ultimately more socially and politically conscious entity. George Romero, who was perhaps the most overtly political of all American horror filmmakers, released Night of the Living Dead in the same year that the death toll in Vietnam was at its highest and legendary civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Not only did Night of the Living Dead’s frank and abrasive approach to violence reflect the growing callousness of the American government towards the expendability of human life in Vietnam, but it also had the courage to cast a Black actor (Duane Jones) as its lead protagonist. One can’t help but feel the hopelessness and anger reflected at the conclusion of the film, when a rural mob of white vigilantes “mistake” Jones’ Ben for a zombie and promptly shoot him dead. Conversely, in the Hollywood studio system, Roman Polanski used his masterful adaptation of Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) as a vehicle for reflection on the growing sexual revolution and women’s fight for equality and control over their bodies.

Arguably the most political decade for American horror was the 1970s. In the years during and following Vietnam, the sexual revolution, and the murderous exploits of the Manson Family (which all but ended the so-called “Love Generation” of youthful exuberance and peaceful protest), renegade filmmakers like George Romero, Wes Craven, and Tobe Hooper pulled no punches. In Wes Craven’s grueling Last House on the Left (1972), a pair of teenage girls travel to a weekend rock concert, only to be abducted by a gang of convicts, taken into the woods, continually and brutally raped, tortured, and ultimately killed. Craven’s refusal to cut away from or sugarcoat his violence was a decision which cost him financing for another film until 1977 (ironically, for the thematically similar The Hills Have Eyes), but would prove inspiring to others who wanted to evoke the unyielding brutality and social unrest of the past decade without having to censor themselves.

Tobe Hooper carved a similar niche with his classic The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), which included horrific and darkly witty commentary on everything from Vietnam to the decline of the American Family (in the form of Leatherface and his inbred, cannibalistic relatives) to the gas shortage. Meanwhile, Romero anticipated government incompetence in the face of national crisis (sounds familiar, right?) with his killer virus movie, The Crazies (1973) and the mindlessness of American consumerism with his zombie sequel Dawn of the Dead (1978). Other independent filmmakers became key contributors to the political/social horror arena as well in the form of underrated classics such as Bob Clark’s Deathdream (1972, which directly commented on Vietnam by focusing on a dead soldier who returns home as an emotionless zombie, literally...) and Larry Cohen’s God Told Me To (1976, riffing on inner city violence and radical cultism). Even the most extravagant studio horror films of the time weren’t afraid to insert political commentary into their narratives: William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) was partly a reflection on what was seen as the decline of fervent religious beliefs and the so-called “death of God.” Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) featured yet another government official (Murray Hamilton’s obstinate mayor) intent on denying the extent of an existential threat. In Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), it turns out that the entire crew of the spaceship Nostromo were deemed “expendable” to extraterrestrial danger by the authority figures in charge of their mission.

By the ’80s, the relentless nihilism of ’70s horror had been somewhat watered down, replaced by flashy “popcorn” sensibilities. In truth, the American horror films of the early ’80s had more of a social and political impact outside of the screen. Case in point: Sean Cunningham’s Friday the 13th (1980), made to capitalize on the slasher film characteristics of John Carpenter’s landmark Halloween (1978), was so successful that it not only spawned its own franchise, but ensured that from 1980–1984, nearly every major studio in America had a hand in contributing to the profitable slasher boom. Furious that Hollywood could “lower” itself to such content, politicians, community leaders, religious leaders, and parents began to organize and protest vehemently. America’s two favorite film critics, Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, set aside an entire episode of “At the Movies” to discourage audiences from supporting films like Friday the 13th, much less offering them any artistic merit. The most directly socially conscious American horror films of the ’80s focused either on the steadily growing AIDS public health crisis or the capitalistic “trickle-down” economic policy popularized by Ronald Reagan. Vampire films such as Tony Scott’s The Hunger (1983) and Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987) eschewed all traditional aspects of vampire mythology, equating vampirism with cursed affliction, transmitted from one unfortunate individual to another much like the AIDS virus. The AIDS crisis also had a significant impact on the “body horror” subgenre popularized by Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg in such works as Shivers (1975), Rabid (1977), The Brood (1979), Videodrome (1983), and The Fly (1986). Because Cronenberg operated largely out of Canada, he receives only a brief mention here.

In 1982, John Carpenter took the blueprint established by the early Cronenberg films and cranked it up to 11 with his adaptation of John W. Campbell Jr.’s Who Goes There? In The Thing, a group of scientists operating out of Antarctica are helpless to stop a bodily invader as it infects their ranks, horribly mutating and contorting them into extraterrestrial monstrosities. Near the tail end of the ’80s, Larry Cohen’s The Stuff (1985) and Carpenter’s They Live (1988) both reflected Reagan’s unashamedly consumerist policies in a transparent, playful manner.

American political horror was not nearly as pronounced during the ’90s. By and large, the horror film in general had fallen by the nation’s cultural wayside as a result of oversaturation of sequels to popular franchises (A Nightmare on Elm Street, Friday the 13th, and Halloween were the chief culprits). As a consequence, many of the early ’90s genre efforts were relegated to TV or direct-to-video releases. The ones that weren’t, notably Rob Reiner’s Misery (1990), Adrian Lyne’s Jacob’s Ladder (1990), and Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991) were pretentiously labeled as “psychological thrillers” rather than horror. It wasn’t until the self-reflexivity and genre awareness of films such as Bernard Rose’s Candyman (1992) and Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994) and Scream (1996) took hold that the commercial American horror film began to find its way back into the public consciousness.

On September 11th, 2001, America was attacked on its own soil for the first time since Pearl Harbor nearly 60 years earlier. This event would leave an irreparable mark on American genre cinema for years to come. Horror narratives reverted back to the more nihilistic and apocalyptic narratives that characterized the 1970s. With the Bush Administration’s War on Terror and the subsequent leaking of information regarding “intensive interrogation” techniques in the Middle East, torture and human cruelty once again came to the forefront of American horror. The oft-derided “torture porn” movement, consisting of films such as Saw (2004) and Hostel (2005), shocked audiences with realistic and stomach-churning depictions of human suffering and torment. Hostel in particular involves a group of American college students attempting to navigate their way around a foreign country (in this case, Slovakia), only to be kidnapped and auctioned off to an organization called Elite Hunting, where wealthy businessmen around the world can experience torturing and murdering another human being for the right price. As such, Hostel cast a dark light on American xenophobia and misplaced patriotic bravado that characterized the Bush years. Meanwhile, while Hollywood was glutting itself with expensive and gorier remakes of classic films ranging from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) to Friday the 13th (2009), independent filmmakers such as Matt Reeves were using the found-footage blueprint laid out by The Blair Witch Project (1999) to helm films such as Cloverfield (2008). In this landmark example of the found-footage genre, an enormous monster ravages New York City while terrified onlookers record the events, conjuring mental images of the horror and chaos surrounding the morning of September 11th.

By 2016, America had already seen its way through yet another presidential administration, that of Barack Obama. The Obama years, despite being marred by economic crisis, weren’t nearly as tumultuous as the Bush years. Regardless, in 2016, the unthinkable happened. America elected its first reality show president in the form of the deeply divisive Donald Trump. While a good portion of Americans lauded Trump’s uncharacteristic approach to the presidency and his often crass ability to speak his mind, the other half of the country remained deeply divided as to whether Trump had the integrity or experience to lead fruitfully. Trump’s controversial approach to politics was truly tested in 2019 when the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) spread to America in a big way. In a turn of events some would consider comparable to the apocalyptic scenarios put forth by numerous zombie films such as Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002), America turned practically overnight into a society defined by social distancing, mask wearing, and massive unemployment.

Even in the proceeding years, the political and social uncertainties of the Trump years weren’t lost on horror filmmakers. Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015) and Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018), widely considered two of the finest horror film offerings of the past decade, both used demonic infestation as a means of reflecting America’s divisiveness and disillusionment with itself. The characters in both The Witch and Hereditary are doomed from the start and are largely powerless to prevent the horrific destiny fate has in store for them. Meanwhile, Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) and Us (2019) tackled racial division and provided a much-needed voice for the Black experience in America within the modern horror film.

It should be a testament to the power and longevity of the horror genre that even COVID-19 couldn’t stop the advent of horror films when the American people needed them most. Filmed in Britain and released through the American streaming service Shudder, Rob Savage’s Host (2020) was shot over 12 weeks and takes place entirely on a quarantine-era Zoom call. Only months later, Netflix released the accomplished debut film of Remi Weekes, His House, which highlighted the struggles of immigrants, reflecting the Trump administration’s callous and unsympathetic treatment of refugees fleeing oppression.

Now, the 2020 Presidential Election is over. The Trump administration’s power over the American people is waning in the midst of the oncoming Biden administration. How will American horror cinema evolve in the coming months? Will the genre become more hopeful as people grow more hopeful, as it did in the ’80s and ’90s? Will it grow more pessimistic as America remains radically divided, as it did during the ’70s and 2000s? What new obstacles and threats will America face in the coming years? Only time will tell, but what remains certain is that the watchful eye of horror cinema will be there to document these struggles. To help the nation cope whilst simultaneously scaring the shit out of them. To record the nation’s struggles and preserve them going forward. And as it always has, to unite the American people through our mutual fears.