[Editor's Note: This article contains spoilers]

What made my heart thump so loudly during Sinners (2025), to the extent that I could barely hear the soul-piercing music, was that the horror didn’t come from fangs or fire, but from the past clawing its way forward.

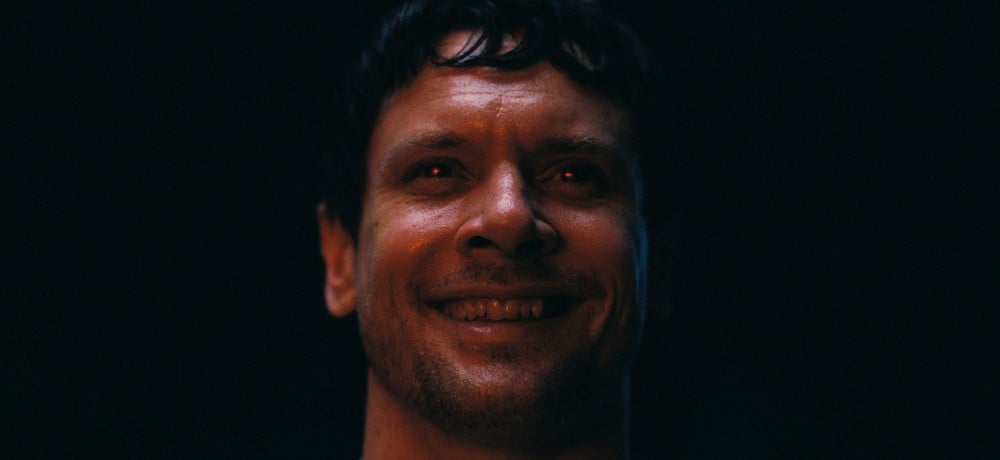

Enter Remick: sharp-dressed, sharp-tongued, and the film’s walking cautionary tale. He’s not just undead; he’s the afterlife of empire. Cloaked in charisma, Remick isn’t a monster but a mirror, reflecting colonial brutality not with critique but with mimicry. He is what happens when the colonised learn the script so well they start directing sequels.

Remick is Irish, carrying the brutal legacy of British colonialism: famine, forced conversions, cultural erasure. He knows what it means to be conquered, how empires don’t just take land, but rewrite history, language, and faith. He knows how spiritual life can be hollowed out, not by fire and sword alone, but by forced conversion, cultural erasure, and the slow bleed of identity until nothing familiar remains.

But Sinners asks: what if the colonised choose power over empathy? Remick has felt empire’s teeth; now he sharpens his own.

He promises freedom because he knows trauma’s terrain. His scars give him a claim. But knowing doesn’t give the right to snatch others’ pain or memories. He weaponizes shared suffering not to heal, but to seize control, wearing his knowledge like a crown to legitimize his rule. Here’s where postcolonial thinkers whisper: Fanon warned that adopting the master’s tools risks becoming the master in disguise. Ngũgĩ taught us language and ritual are survival blueprints, not mere culture. Césaire wrote that colonialism doesn’t just destroy; it teaches its victims how to destroy.

Remick is that destruction in slow motion. He hoards pain, turning it into dogma. His theology serves no god but himself. He speaks of justice but auditions for divinity. The pulpit becomes a throne. The communion, blood.

And Sammie, his voice, music, and spirit, is the bridge Remick wants to steal. Through Sammie’s culture, he wants to reach his ancestors, but not through understanding, through possession. He treats Sammie’s spirituality like a key to unlock his past. Who better to steal from than another victim of empire? Another haunted body.

Remick doesn’t just feed on bodies; he feeds on meaning. He chews through symbols, stories, and sacred traditions like snacks. Blues music, ancestral rituals, resistance hymns become props in his one-man show of “redemptive” violence. He doesn’t understand history; he doesn’t want to. He just consumes it. And here’s the gut punch: it works. He’s charming. Almost messianic. Sinners doesn’t make Remick a caricature villain; it makes him believable. That’s the horror. He’s not an outlier. He’s the pattern: the colonised who survive empire only to replicate its worst parts. Not the invader, but the inheritor.

The film’s music drives this home. Early on, Annie talks about people with a gift for music so true it can conjure up spirits from the past and future. In Sinners, song isn’t background; it’s archive, memory, resistance. The drumbeat under the lash, the hymn behind the missionary, the sound of survival when everything else is erased.

One of Sinners’ most jarring moments comes during the “Rocky Road to Dublin” sequence, where Remick, freshly fed and euphoric, begins to Riverdance. Then the others join in. Vampires, already turned, clap and sing along, their voices rising in eerie unison. It's not celebration; it's conquest. This isn’t Irish culture preserved; it’s Irish culture repurposed. Repackaged. Remick’s empire doesn’t erase culture; it reanimates it with new, clingier claws. The horror isn’t that they’re dancing; it's that they’ve all learned the steps to his rhythm.

Delta Slim, played by Delroy Lindo, delivers a line that echoes through the entire film:

“Blues wasn’t forced on us like that religion. We brought that up from our own.”

It’s a brief moment, but one loaded with power. In a world where nearly everything sacred to Black communities has been stolen, rebranded, or used against them, language, land, belief, and blues stand untouched. Not because it was hidden, but because it was too rooted to be severed. It didn’t come from outside imposition like Christianity. It came from within.

And that’s exactly why Remick wants it. Or rather, why he wants Sammie. Remick isn’t after blood alone; he’s after meaning, access, power. And Sammie’s music is the key. The vampires in Sinners inherit memory through blood, and Remick believes that by taking Sammie, he can reach his own ancestors, feel his own roots.

But the film doesn’t let him. In a devastating, defiant moment, Slim sacrifices himself to save Sammie, slitting his arm to lure the vampires away. His death isn’t just a tactical move; it’s a final act of guardianship. He protects not just a boy, but a legacy. He ensures that Remick can’t get what he came for.

Near the end comes a communal prayer, Sammie’s prayer. All voices singing a hymn forced into their histories. A song born of missionary zeal, repurposed as a plea. It should redeem. It should unite. Instead, it devastates. It doesn’t save Sammie or stop Remick. Even the vampires sing it, a grotesque echo of faith once weaponized to conquer them all.

The ritual fails not because the music lies, but because the system behind it was never meant to save. Christianity, thrust on Irish and Black communities as domination offered as faith, but enforced as a weapon to dismantle their spiritual traditions, overwrite their cultural identities, and justify colonisation, becomes a haunting reminder: shared suffering doesn’t guarantee shared salvation. When Remick dunks Sammie in water, it’s no mercy. It’s a baptism. Not rebirth or cleansing. Just another cycle. Another life sacrificed so someone else can feel closer to God.

The film lays bare the trap: pain unexamined curdles into power. Memory unreckoned mutates into myth. If we treat our trauma as a pass to rewrite others’ trauma, we become the ghosts we run from.

History isn’t a horror you outrun; it’s a mirror. Stop looking and you start reenacting. Hauntings don’t begin with chains; they begin with entitlement: believing your suffering crowns you king and gives you the right to take from others.

But ghosts of the past don’t need thrones, they just need hosts. And Remick? He’s waiting for you to open the door. And when that happens, the monster isn’t the one we feared. It’s the one we trusted.