Director, writer and producer Mark L. Lester (26 November 1946, Cleveland, Ohio) will forever be tied to a handful of quintessential ’80s hits and cult films, among which a place of honor goes to the Joel Silver-produced, over-the-top Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle Commando (1985). A film which irrupts in cinema theatres after another two of the director’s most well-known efforts: Class of 1984 (1982) and the Stephen King adaption Firestarter (1984). In the following interview, Lester reminisces on how he transitioned from drive-ins to the Hollywood studio system.

Let’s start with a question on the narrative structure of your films. Within the last act of some of your biggest hits there will be a total narrative suspension, and what will take place is essentially a completely cinematic mechanism, a cinematic mayhem if you will, that often becomes playful and deconstructs any pretention the film has built upon previously. I’m thinking of films such as Firestarter (1984), Commando (1985), and Showdown in Little Tokyo (1991).

Mark L. Lester: I want to start by saying that many of my films have a revenge theme. It’s something I’ve only recently noticed, but revenge and conflict are elements that often return in my stories and the final act is usually the resolution of that conflict. I come from a very visual, not a word-based, way of conceiving films, and to me that resolution must articulate itself visually and in the most spectacular way possible. What you are underlining is essentially the manifestation of the character’s, or characters’, inner anger and frustration, which end up exploding. I think Class of 1984 (1982) is a perfect example of this. The finale is a release valve for the protagonist, but also for the audience. You hold it all in and then unleash at the end. So yes, this is both narratively and visually a recurring thing in many of my films, with maybe a few exceptions like Roller Boogie (1979) or maybe a few of my comedies... Although actually I think I direct my comedies pretty much like I direct my action films, with that same dynamism and use of big punching finales.

How do you choose your projects, and specifically how did you choose them in the ’70s and ’80s?

Mark L. Lester: Well, throughout my entire career my worry has always been to work, to have projects coming in, to keep the flow going. I have that Howard Hawks mentality, you know, the working director, the journeyman, and like Hawks I’ve always wanted to do different films, dwell in different genres. I remember many years ago, I went to a lecture at UCLA where Howard Hawks was speaking, and he said, “They would deliver scripts like the morning newspaper.” In those days they made 80, 90 films. Alfred Hitchcock made 90 films, in fact… People don’t realize or tend to forget that he had made 30 films before directing The 39 Steps (1935).

Right away, at a very young age, I decided I wanted to be very prolific, I wanted to be like an old Hollywood director. To me it has always been about finding ways to keep scripts coming in. First of all, I did that by saying a lot of “yeses”. Every time I was offered a film, like Commando or Firestarter, I would say yes right away. In the meantime, I would look around and based on what I felt could work, I developed my own projects like Class of 1984. In the ’90s, that is what I did for the most part, choose and develop products that I would then produce. Tapping into what was happening in popular American culture has always been my starting point, even with commissioned projects.

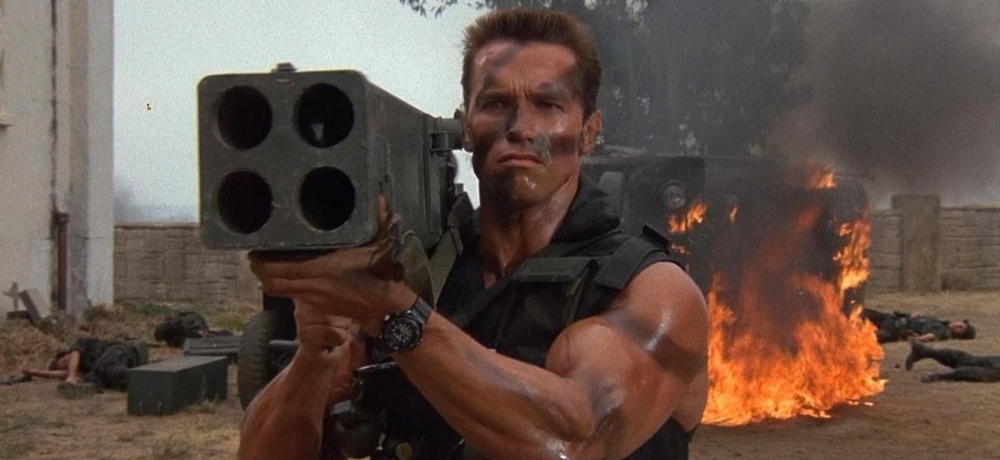

Commando, for example… at that time there was a rumor that under Ronald Reagan, Nicaraguans had an island not far from the Californian shore, where they would train guerilla-like soldiers to send back to Nicaragua. Based on that I decided to add this place, this small island, where we find this factory, a warehouse full of weapons… That was not in the original script. So, I was always pulling from real-life elements, political, social, or otherwise.

Extreme Justice (1993) stems from what was happening within the LAPD, which I met and talked to during the writing stage. Blowback (2000) is basically a collage of all sorts of FBI and US intelligence scandals and rumors. So I was making relevant films for a broad audience while continuing to work as much as possible. This has been my philosophy, if you will, if we want to call it that. As many as possible, as fast as possible, you know what I mean? Now, if a director reaches 35 films, that is a massive amount, because now it’s so hard to actually set up a project, there is just so much competition out there. If a guy manages to make a film every three or four years, he’s doing well, right? You never seem to have everything: sometimes you have money, but no good project. Other times you have a script, but nobody to finance it. You can’t win, but you have to keep pushing forward.

You start out in the ’70s in exploitation films. That’s a period you don’t often talk about.

Mark L. Lester: Nobody asks me about those years. What’s funny… and nobody has ever fully realized the extent of my plans, Steel Arena (1973) became upon release a drive-in film, but actually it was never conceived for that circuit. That was my first feature-length film and it’s part of a trilogy, my Americana trilogy. Later I did Truck Stop Women (1974) and Bobbie Jo and the Outlaw (1976). I set out from the word go to make a series of three films that in my mind captured the spirit of the American life in that period. I only later understood the value of the drive-in circuit.

You know, in many ways drive-ins were the DVDs of their time. Affordable, there were many of them and easy to go to. That period and those films gave me the possibility to be known. I got them screened and showed them to studio executives, but the film that definitely gave me a boost in the right direction was Roller Boogie, which was sold to United Artists. That film became their Christmas release, their main film for that season with 50,000 theatres showing it and a massive publicity campaign. It was the first time a film of mine received that kind of treatment.

You followed Roller Boogie with a privately funded film.

Mark L. Lester: Yes, Class of 1984 was independently produced because it was considered a highly controversial project. It was a hit overseas, here in Europe, but no studio wanted to touch it. It was just too controversial and it was passed upon by everybody. I organized a screening at Warner and they went, “It’s well made, but we can’t deal with this sort of film, no theatre will show it. You have kids dying and being shot at in classrooms”.

So I went off to United Artists Theatres and screened it again for the head of it. He watched it and turned to me, “Sure, I will screen this. Hell, I will put it in 1,000 theatres straightaway!” I answered that I would go back to Warner and tell them immediately. He went, “Are you crazy? You’re the distributor now and you have just booked this flick all over the country. Congratulations!” “What?” “You heard me!” He gave me a check for 500,000 dollars immediately to cover the income. “Why would you go to Warner? You can make serious money here. At the moment I have The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982) out there and it’s making no money. I’m going to pull it out and put your film in its place.”

The film ended up opening in New York three weeks later and made a million dollars in its first week. Roller Boogie first and then Class of 1984 are the two films that put me on the map. In fact, after that I was approached to direct Firestarter. My relationship with the studio system is a completely different matter and it really began with Commando, which is 100% a studio film. Although my studio career didn’t last much, only a few years. That system is slow and has a lot of rules and as I said, I like keeping the flow going. Studios are big corporations and I’m an independent in fact and at heart.

Do you believe Class of 1984 has maintained its controversial nature?

Mark L. Lester: No, it hasn’t, not really. Now it’s tame. I mean, after Columbine, it’s tame. In the beginning of the movie, if you look at it, it opens with a card that says, “Last year, there were 280,000 incidents of violence by students against their teachers and classmates in our high schools. Unfortunately, this film is partially based on true events.” So there was a warning at the beginning of the film that was very prophetic because the warning didn’t even comprehend what actually would happen.

Did you have complete liberty on Commando?

Mark L. Lester: Yes, absolutely. I pretty much did what I wanted. I had a supportive group of writers and yes, I had complete control over the project. I created the film from scratch in many ways. It was a time in which the studio… they had no movie, the project had been in limbo for quite a while before I put my hands on it. They had sold it to Marvin Davis, and they had a guy called Larry Gordon who used to be with American International Pictures. He is the person I met on my first meeting for that film. I knew him from all the exploitation films he had worked on in the ’70s. On that first meeting, he goes, “Do you remember that Jim Brown film in which he goes down to Mexico to take revenge on the guys who framed him? Slaughter (1972). Do that! Commando is that Jim Brown movie.” If you look at the film, it is an exploitation film, really. Commando is a big-budget exploitation film from the ’70s. Which is what was happening at that time, I mean even before then, in the early ’80s: take these drive-in, grindhouse flicks and make a bigger version of them.

Commando is so aware of what it is and it’s possibly the first film that starts deconstructing the persona Arnold Schwarzenegger had built for himself until that moment. It is nearly a modern peplum, like the Italian mythological epics. Steve Reeves and Dan Vadis throwing down cardboard columns... The opening sequence is so emblematic of this…

Mark L. Lester: Yes, I agree. A reviewer from the L.A. Times got it right when he said, talking about Truck Stop Women, that “he’s a pop-art Andy Warhol…. he’s Andy Warhol for cinema.” Although Warhol made 80 films... That said, it was true. That early on I was developing this approach to the medium, which was very based on hyperactive stylized pop art, comic book hyperbole. I was never interested in reality. I inserted in my films, as I mentioned previously, elements connected to reality, but then changed them into what is essentially a comic strip, a live-action comic strip. Commando is that basically…

You mentioned the opening scene; well I took that from the Leni Riefenstahl imagery. I had been a programmer at a repertory cinema, so I was like, “Yes, I will put that Aryan Nazi-like masculine figure coming out of the clouds.” All these images I had been accumulating, attaining to all sorts of things that came together in that film. In many ways, it’s the culmination of all my previous work, assembling these pop-like influences. Somehow a perfect movie came out of it. I consider Commando and Class of 1984 to be my perfect movies. They just worked out. There is no way to predict something like that and you never realize you are working on a classic. I want to go back to Howard Hawks. He once said, “I didn’t know these were classics, I was just working on movies.” John Ford thought The Searchers (1956) was just another western. It is the same thing with me. I was just doing my thing, bringing my style to the story, but it fit perfectly with that ’80s aesthetics. That film has everything in it, from punk rock to Aryan Nazis!

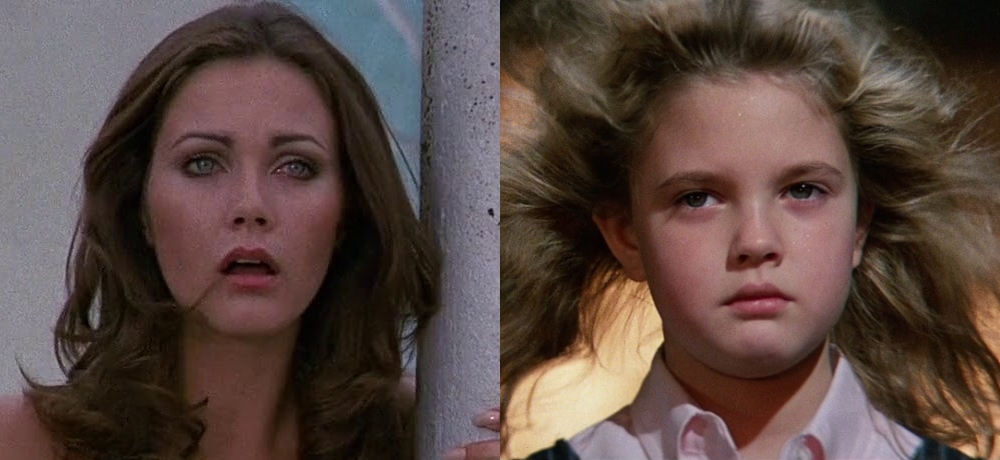

We are mentioning many different films, but our time is limited and I want to concentrate on Firestarter. How did that film come to be?

Mark L. Lester: Originally John Carpenter was going to direct that. There was a script that was written, I forget who wrote it. Then the budget was way out of line, like $15 million. This script had no relationship to the book whatsoever. They did not want to shoot it for that amount of money, so Dino de Laurentiis came to me and said, “I read the book. Can you make a treatment out of this?” So I brought in Stanley Mann, who I knew, and when we wrote the treatment, we styled it after the book exactly scene for scene. We gave it to De Laurentiis, and he said, “Well, this just follows the book exactly…” “Well, yeah, of course! You paid a million dollars for the book”, I said.

So, within three weeks the script was written, and we had a green light from Universal to make the film just off the script, which was identical to the book. That film is absolutely the most difficult film I worked on. We took one whole week working nonstop to finish the farm attack sequence at the end. It was all pretty nightmarish. What you see in that last act are practical effects. The fireballs… that’s not CGI. Back then, we actually created fireballs that could fly through the air! They were on a wire and could crash into buildings. We had people on fire that were on trampolines that had to flip through the air. It was very dangerous. All the effects were done right on the set—it was a pretty intense thing to do then.

How was your relationship with Dino De Laurentiis?

Mark L. Lester: I think Dino De Laurentiis is one of the best people I have ever met in my life. He taught me a lot of stuff. He knew cinema and the film industry inside out. I have never met someone like him since. I was thrilled to work with Dino because I was a great admirer of all the work he had done with [Federico] Fellini. What I did not expect was that he was an extremely hands-on producer. He really took care of every part of the filmmaking process.

I have one great regret tied to him, that I turned down the possibility of directing his next Stephen King adaption. He had asked me to direct Cat’s Eye (1985), but I had already signed a contract for another film. He was simply amazing and I cannot see how anybody could ever say anything different from that. I recently had dinner with Martha, his daughter that I met on the set of Firestarter, she was the associate producer on that. I asked her, as we were having dinner, how Dino was in his nineties, just before dying, and she told me they were having a meeting discussing the next film and he asked to go and have a nap, one he never woke up from. He was working right until the end. The man loved films deeply and I can only say he was an amazing human being.