[This piece was co-written with Gian Giacomo Petrone.]

[This October is "Gialloween" on Daily Dead, as we celebrate the Halloween season by diving into the macabre mysteries, creepy kills, and eccentric characters found in some of our favorite giallo films! Keep checking back on Daily Dead this month for more retrospectives on classic, cult, and altogether unforgettable gialli, and visit our online hub to catch up on all of our Gialloween special features!]

"The old dies and the new cannot be born: in this interregnum, the most diverse and morbid phenomena occur."

In this maxim penned by Italian Marxist theorist, writer, and politician Antonio Gramsci, depleted of its penetrating political significance, but not of its universal character, lies a stringent and clarifying reading of that pre-eminent period of popular Italian cinema, between the end of the ’70s and the beginning of the ’80s. A short history of this irreversible crisis finds a first turning point in the Year of Grace 1974, and specifically in the Constitutional Court ruling 225, which authorized cable broadcasting for private companies; a second judgment, no. 202 in 1976, also of the Constitutional Court, will sanction the first liberalization of the ether, albeit only on a local level. In this context it is not obviously essential to examine the entire recent history of Italian television, with the allocation of RAI to the three major parties (DC, PSI, and PCI) and the advent of the Berlusconi mass media empire; it is enough to remember how, from the two above-mentioned rulings, the overall perspective of the relationship between cinema and television on the one hand, and between spectator and image on the other, changes radically and definitively.

Private broadcasting channels go from roughly 250 films in 1978 to about 600 in 1980, while local and national palimpsests offer a different film experience, proposing both private and free unrestricted viewings in your own home, although interspersed with advertising and lacking the unreachable charisma of the big screen. Between 1980 and 1985, the number of filmgoers halved. So then, the "old which dies” is in this case Italian genre cinema or perhaps Italian cinema as a whole. We can also discern, when nearing the new millennium, the progressive aging or disappearance of the great directors and actors who had reigned supreme during the most fertile and precious seasons of our cinema. The "new that cannot be born" is a more distant season of that cinema, one that until the end of the ’70s had been capable of renewing itself and inventing film categories and native genres as well as re-elaborating those coming from other latitudes and cultures, not only by interpreting the original themes and styles, but also by developing new ones so as to form a paradigm and a model both in Europe and beyond the Atlantic.

Indeed, since the 1980s, the ideological and productive autonomy of the film industry, which had characterized the decades from 1945–1979/80, was lacking. It is television that dictates law. It enforces the collective imagery, themes, and subject matters. There is a great migration of directors and workforce that move from the big to the small screen while many film projects are compelled to deal with the uncertain identity of their ventures, which clearly had to be conceived both for the film theater and for television, a double fruition that might prolong their lives, but often ends up altering language and content. At the same time, many of the major directors of the 1970s (Lenzi, Castellari, Martino, and Margheriti) end up in smaller productions, mostly conceived for the least demanding foreign markets. Moreover, perhaps the most alarming aspect is that in the Italian landscape, the necessary and organic generational replacement is lacking. In particular, genre cinema is incapable of communicating new forms of expression and above all, of becoming an interpreter of its times: the “poliziesco” implodes, stagnating in cinemas, but no longer as a symptom of the socio-anthropological malaise of the country; for its part, the giallo/thriller also ends up blunting the cynical and brutal tones that had characterized it. In short, until the end of the 1970s, popular cinema is still an excellent interpreter of the spirit of the times, succeeding in symbolically reworking the idiosyncrasies and anxieties of the country, as well as succeeding in outlining the ghosts and shadows that lurk on the horizon of everyday life and the dusk of the Italian consciousness.

Some examples, so as to have a concise overview of the “best” gialli produced in the ’80s, therefore without digging into the lowlands, can be found in Mystère (Dagger Eyes, aka Murder Near Perfect, 1983) and Sotto il vestito niente (Nothing Underneath, 1985), both by Carlo Vanzina. These are reasonably well-conceived titles, at least compared to many of other contemporary productions, but with the original defect of never giving the impression of authentically believing in the critiques being put in place. The world of high-class prostitution in the first case and that of the world of fashion in Milan in the second, are never really questioned, but rather become the subject of passive hagiography and complacent visual subjugation. Vittorio De Sisti's Delitti e profumi (Murders and Perfumes, 1988), and Caramelle da uno sconosciuto (Sweets from a Stranger, 1987) by writer Franco Ferrini (who also wrote De Sisti’s film) can also be placed on the same level; two titles that are saved, technically speaking, from the general ignominy, but that smell too much of television, both in the acting and in the staging.

A common denominator of many of the thrillers of the ’80s can be found in the elaboration of an image that is devoid of darkness, chromatic conflicts, visual tension: extreme coloristic accentuations, the boundaries of a frame that cannot and does not want to show explicitly, but only fragments of reality: these are all sworn enemies of television, which wants hyper-visibility and clarity. Worth saving, within the decade in question, are a handful of titles made by directors of various extractions and backgrounds; works of undisputed masters such as Lucio Fulci and Dario Argento in addition to other contributions from the few and worthy heirs of the great tradition of Italian giallo, namely Michele Soavi and Lamberto Bava. It should also be noted how these films are, more often than not, a sort of detritus, perhaps of great class, in the career of the various directors concerned, who give their best within the ’80s, mostly in horror.

We can notice many contradictions imbedded in the giallo of the ’80s by just taking two titles as an example: Carlo Lizzani's La casa del tappetto giallo (The House of the Yellow Carpet, 1982) and Un delitto poco comune (Phantom of Death, 1988) by Ruggero Deodato. Already the juxtaposition of Lizzani and Deodato in an analysis on Italian cinema may sound eccentric, yet it is a sign of the mingling and hybridization, perhaps of the confusion that reigns in this "post-apocalyptic" perspective of Italic cinema. Of course, the two films in question have little to do with each other, and yet they are two different symptoms of the same situation. Lizzani, one of the leading filmmakers of Italian civil cinema, with The House of the Yellow Carpet, confronts a kammerspiel thriller with a vaguely Buñuelan flavor, where the theatricality of the staging matches the meta-textuality of the plot thanks to the awareness of the two main characters (Erland Josephson and Milena Vukotic), who each play a part in order to deceive a young woman (Béatrice Romand) on behalf of her husband (Vittorio Mezzogiorno). The mise en abîme of the theatrical element united with the filmic language works well at times and despite the too many and sometimes foreseeable twists along with the probably exaggerated and overwhelming ambitions of the film, the result is secured thanks to the excellent cast.

On the other hand, Deodato, better known for his (remarkable) cannibalistic exploits, draws the strength of his film—in many respects similar to the giallo-slasher already noticeable in the ’70s—from the story’s premise: the killer (Michael York) is a good-looking 35-year-old man, but sick with progeria, a rare disease that manifests itself especially in childhood and which leads the individual to age exceptionally fast, due to a rapid degeneration of the tissues. The result is a curious giallo with an elusive killer, owing to the rapid transformation of his looks and extremely vulnerable state because of his personal drama. Phantom of Death is distinguished by both the ability to blend the morbid fascination of the murders together with the shadows of an existential tragedy, and above all, by disassembling one of the axioms of the decade, that is to elevate appearance as the main synonym of success. A further and last film to be considered in this first set is Copkiller (a.k.a. Order of Death, a.k.a. Corrupt, 1983) by Roberto Faenza, a thriller/noir more American than Italian—and not just for the New York setting—where the metropolis interacts closely with the characters, becoming a kind of incubator/midwife of their impulses and a backdrop to their impotence in reacting to threats which are perhaps more in their mind than elsewhere. With Faenza’s film, Harvey Keitel’s character seems to be the first rehearsal for his role in Bad Lieutenant (1992) by Abel Ferrara. Completing the interesting and colorful cast are Leonard Mann (alias Leonardo Manzella) and John Lydon, better known as Johnny Rotten of Sex Pistols fame.

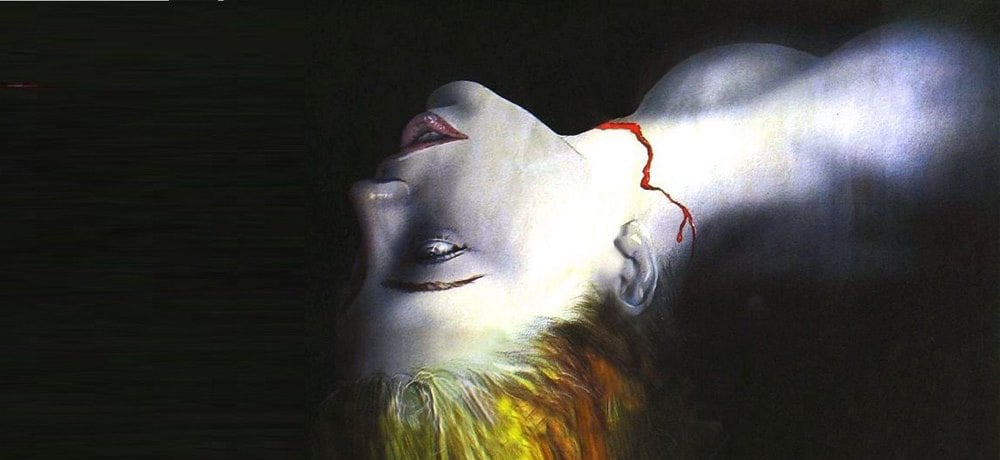

Fulci and Argento, on the other hand, in the purely giallo context of their productions of the ’80s, seem to walk along two parallel paths in the imagery of the time, and literally demolish it piece by piece. Fulci, between 1982 and 1984, directs his only two giallo films of the decade, productions that seem to be at complete odds with each other. Like in most of Fulci’s films from this period, in Lo squartatore di New York (The New York Ripper, a.k.a. Psycho Ripper, a.k.a. The Ripper, 1982), the usual iconic extremism dominates, that is to say the one most widely used in horror, whereas in Murde Rock- uccide a passo di danza (Murder Rock- Dancing Death, 1984), violence does not occupy the canonical murder sequences, but moves "politically" on the verbal (a very rare case in Fulci’s cinema) and auditory side. The New York Ripper is a 24-karat Fulci, both in the very personal and often "subversive" use of the grammatical convention of shooting, with "impossible" POVs, surgical zooms, bright chromaticity, and paroxysmal and exasperated violence. Nothing similar can be found in Murder Rock: the directorial style is more fluid and less syncopated, the rhythm is more relaxed and less aggressive, while the nodal point is no longer in the staging of a series of murders, but in the faithful description—this, yes, pervaded by the iconoclastic fury of the Roman director—of the behind-the-scenes of an elite dance school painted like a nest of vipers, starting with Candice Norman (Olga Karlatos), the dance teacher, who then turns out to be the assassin of her own pupils. In Murder Rock, true violence resides in the dogmas of competition, exposed in a monologue by Karlatos' character after the first murder, and in the description of the school, reminiscent of a kind of morgue.

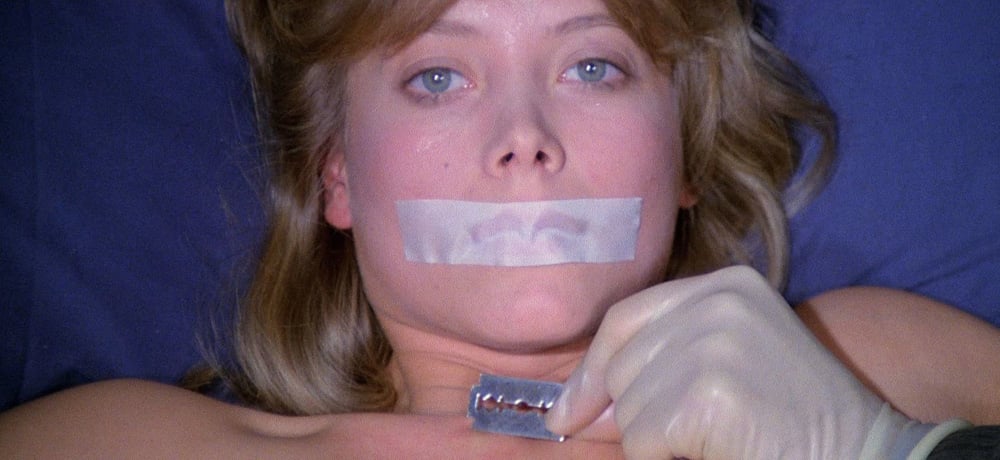

As far as Argento is concerned, the stylistic and visual change perceived in Tenebre (Tenebrae, a.k.a. Unsane, 1982) with respect to the previous horror diptych, comprising Suspiria (1977) and Inferno (1980), has been much discussed and contextualized. Many of Argento’s scholars have focused on his return to giallo after the parenthesis with pure horror, as well as on the decisive luminary, chromatic, and narrative change that invests the 1982 film. It is probable, however, that it is not so much Argento to have changed as much as the times and history, even that of cinema. The transition from the diptych, with its chiaroscuros, the chromatic extremisms and spiral-shaped narrative construction, to Tenebrae with its all-pervading light, the coloristic "flattening" on lighter or neutral shadings, the more traditional coordinates of the whodunit structure, reflects not so much an autonomous change of style for Argento, as much as his tuning into the new spirit of the time, with unusual aesthetics and innovative mode of staging, which also provide a much closer and synergistic tie between different media such as cinema and television, with their respective iconographic horizons. All this is intelligently conceived however, through a persistent linguistic conflict, since in Tenebrae, the synergy between media and the expressive innovation is manifested only by contrast. Here, then, the over-illuminated visual articulation of the murders and suspenseful moments, even in nocturnal contexts, creates a short-circuit when in opposition to the fierce and extreme brutality of the violent deaths. Likewise, the orderly and aseptic geometry of the environment of Rome's EUR area conflicts with the deflation of the murderous drive.

Even eroticism, almost absent in the director’s previous films, has a fair space in the narration, not simply as a mere voyeuristic pleasure, but rather as a harbinger of the psychic drift of the two killers at the center of the story, or as the trigger to their actions. In fact, if the first of the two (John Steiner) is a delirious and uncompromising television journalist (here's how Argento sees television and its representatives: bigoted, incoherent, and ridiculous moralists) with probable repressions of a sexual nature, while the second, film star Peter Neal (Anthony Franciosa), is moved to murder—and probably also to his creative activity—because of an original trauma, also of a sexual nature. In short, it can be argued that Argento, in Tenebrae, seems to resort to the aesthetic of the new decade to multiply the subversive possibilities of his cinema; it will only be from the ’90s that his iconoclastic charge will begin to collapse, with a progressive softening of the tones of staging and narrative, which will coincide with the irreversible weakening of his gaze, one that is still fully functioning in Opera (a.k.a. Terror at the Opera, 1987).

It has been observed so far how the best of the 1980s giallo production orbits around well-known names of the genre, and how the "new" has difficulty in finding its way. This difficulty is also evident in the only two authentic Italian heirs of giallo, Soavi and Bava Jr. In the case of Soavi, there is a single title attributable to giallo, Deliria (StageFright, 1987), a film that fully reflects the zeitgeist of the decade as well as containing the typical characteristics of a debut. In fact, StageFright shows that Soavi absorbed not only the lesson of the great Italian thriller masters, such as Mario Bava, Fulci, and Argento, but he has also kept an eye on the fundamentals of overseas capers (Clark, Cunningham, Carpenter, as well as De Palma and above all his Phantom of the Paradise). StageFright already shows the great technical qualities of the Milanese director in wisely exploiting a small budget, a non-superlative cast, and in highlighting the tight and narrow spaces with an elegant and essential direction. The true added value of the film is, however, in the pre-finale, when the killer in the (fake) theater in which the massacre takes place (a further example of meta-textuality in the giallo of the period), has on the stage the slaughtered bodies of actors/victims and technicians with the help of mannequins (replacing the true ones that were part of the choreography): the result is a kind of macabre dance, which acts as an emblematic sign, synthesis, metaphor, and perhaps epitaph of a genre in which the actor is always and only a body, a doll-mechanism to be made into pieces, to be taken apart and recomposed.

Lamberto Bava, for his part, probably incarnates at best the problems of the ’80s, being divided between the lessons of previous teachers and the need to explore a new language and new approaches to staging so to penetrate the nascent hegemony of television and, more generally, the aesthetics of the new decade. In the four giallo films that mark his career in the 1980s, it is possible to note that, besides topoi and well-known styles, efforts are also found in visual and narrative solutions that are the faithful mirror of those years of concealment and inevitable folding on self-referential, meta-textual, and theoretical components of film construction. Macabro (Macabre, 1980), La casa con la scala nel buio (A Blade in the Dark, 1983), and Morirai a mezzanotte (Midnight Killer, a.k.a. Midnight Ripper, a.k.a. You’ll Die At Midnight, a.k.a. Carol Will Die at Midnight, 1986) constitute an ideal and unequal triptych of alterations/dysfunctions, and a sensitive reception of reality.

Macabre is not only a small gem of the grotesque and the surreal (thanks also to the Avati brothers' contribution to the script), but also an articulate essay on the perceptual and/or cognitive abnormalities which afflict the eye and mind as well as a remarkable reflection on what is perturbing. The abnormal triangle between the young blind tenant Robert (Stanko Molnar), the mature but pleasing landlady Jane (Bernice Stegers), and a mysterious individual with whom the woman spends her noisy, sex-filled nights develops through the wise use of filmic language, where the sonorities, the spectator's identification with the blind protagonist (who plays the role of detector in the narration), and the spiraling intensity of the orchestration go hand in hand with the development of the tale. The progressive descent into the macabre is always intelligently guarded by the mocking taste for the bizarre, typical also of Mario Bava's films. The touch given by the presence of another unhealthy character, the pernicious and murderous Lucy (Veronica Zinny), the teenage daughter of the woman, adds to this pitch-black and well-constructed story, which, despite its originality, still looks at Lamberto Bava’s paternal spirit, without succeeding (fortunately) to transcend it entirely.

A Blade in the Dark abounds with references to that small group of "perceptive-cognitive" and meta-cinematographic giallo examples that develop from Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-up (1966) onwards and which include, among the most illustrious titles, The Conversation (1974) by Francis Ford Coppola and Blow Out (1981) by Brian De Palma. Midnight Killer instead looks back at the Italian examples of the ’70s, with an eye on I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale (Torso, 1973) by Sergio Martino. Both of them are pervaded with the ghost of Argento, that is repeatedly called into question and even "robbed" of one of the basic ideas of L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970) for its most important sequence. The overall impression is that in these two films, although with quality direction and with solutions that are far from trivial in the staging of the key events, Lamberto Bava is struggling to break free from the shadow of his Italian and foreign models, being forced, at a time of decadence of the genre, to resort to clichés, to the weary schemes of (once innovative) ideas now reduced to the rank of forced passe-partout solutions, faded copies of images coming from another era.

---------

Keep an eye on our online hub throughout October for more of our Gialloween retrospectives!