[This October is "Gialloween" on Daily Dead, as we celebrate the Halloween season by diving into the macabre mysteries, creepy kills, and eccentric characters found in some of our favorite giallo films! Keep checking back on Daily Dead this month for more retrospectives on classic, cult, and altogether unforgettable gialli, and visit our online hub to catch up on all of our Gialloween special features!]

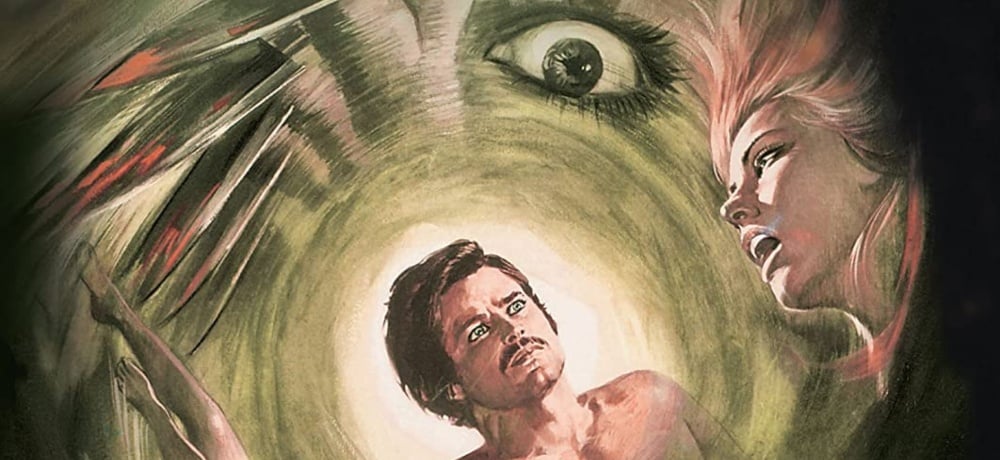

“Dead? I’m dead? Can’t be. I’m alive. Can't you tell I'm alive?” These are some of the first thoughts that cross the troubled mind of Gregory Moore (Jean Sorel) at the beginning of Short Night of Glass Dolls (aka La corta notte delle bambole di vetro). And Gregory has a right to be troubled. That’s a common response when someone is fully aware they're being placed on a cold metal slab in a morgue in Prague. But the problem is that Gregory hasn’t really woken up—not entirely. His brain is awake, but the rest of his body isn’t. In true nightmare fashion, he can’t move a muscle in the morgue. Even his heart has seemingly ceased beating, although his wide-open eyes can see the doctors evaluating him, and his brain knows that his next destination could be the autopsy table.

Although his mind is awake, Gregory's memory is still foggy, and he can’t remember just exactly how he got into his near-dead state. With his current situation growing evermore grim, Gregory searches his thoughts for clues, taking viewers into his recent past on a wild ride that will hopefully rekindle his memory… and bring feeling back to his fingers.

As it turns out, Gregory is well-equipped to search for clues, even within himself. As an American journalist living in Prague, it’s what he does for a living alongside his ex-girlfriend Jessica (Ingrid Thulin) and friend Jacques (Mario Adorf), although before he found himself on the examiner’s table in the morgue, he had been spending less time at the office and more time with his current lover, Mira (Barbara Bach). That all changes, though, when Gregory is summoned late one night for a false tip on a big news story, only to come back home and find that Mira has vanished from his apartment without a trace, with her passport and belongings left behind.

And so begins Gregory’s own investigation into Mira’s disappearance, a disappearance that the local police don’t seem to care that much about. They tell Gregory that in their city, young women go missing all the time. This only encourages Gregory to take the case on himself, and the deeper he digs, the more connections he finds between the local vanishings, with all signs pointing to a creepy, high-end socialite group known as Klub 99, where chamber music may not be the only form of entertainment…

Director Aldo Lado (who co-wrote the screenplay with Ernesto Gastaldi) takes us back and forth between Gregory’s investigation from the past and his current paralyzing predicament at the morgue. Both storylines are hypnotically compelling with their own creeping sense of dread, so the constant back-and-forth actually enhances the suspense rather than taking away from it. Also enhancing the tension is cinematographer Giuseppe Ruzzolini, who meticulously frames everything and everyone. This is one of those movies you have to watch with It Follows eyes, because characters in the background could come to the forefront of the mystery at any moment, especially as Gregory’s paranoia increases with every clue, with the close-ups on his wide eyes (which will soon be incapable of blinking) becoming more frequent as he loses himself in the city’s secrets.

It turns out those secrets have a bloody way of being kept, too, as the bodies of Gregory’s friends and informants begin piling up the deeper he dives into Klub 99. If you’re playing giallo bingo at home, you won’t have any black-gloved killer square to fill this time around, but make no mistake, there is a murderer (or murderers) on the loose. Going against the blood-spattered giallo grain, Lado doesn’t hide the killer’s face behind a mask or focus only on his hands. Instead, he shows us the killer’s steely gaze as he watches Gregory’s every move. Sure, he does his dirty work under the cover of night and goes out of his way to blend into the general public, but this killer isn’t scary because of a hidden identity. He’s scary because he hides in plain sight. He’s scary because he’s only the muscle of a much larger, much more powerful operation, and he’s scary because even though Gregory knows that he’s being watched by this enigmatic man, there’s not a damn thing he can do about it.

Gregory is, after all, a stranger in a land that’s strange to him… and not always friendly. In the eyes of the local police, he’s a foreigner who’s spent a little too much time around dead bodies—a pesky American journalist who asks too many questions and sticks his nose where it doesn’t belong. Time and time again, Lando and Gastaldi tap into a xenophobic theme. Whether he’s dealing with the police or trying to worm his way into Klub 99, Gregory is treated as an outsider. Characters who hold positions of power in the film despise Gregory for being a foreigner and for being a journalist. Watching this movie in 2020, nearly 50 years after its initial release, it’s unfortunate how timely these themes still are today. You get the sense that Gregory and his friends are in just as much danger because of their nationalities and profession as they are for being embroiled in a missing person investigation. The fear of the outsider (and fear of being persecuted as an outsider) dominates the narrative. Even when Gregory is presumed dead, he’s an outsider, the only living human on the slab in a morgue filled with dead bodies, struggling to find his place in his newfound purgatory. Is he dead? Is he alive? Unable to communicate with the living or the dead, it’s hard for him to know for sure.

In the storyline where Gregory is not awaiting the knife on an autopsy table, he discovers that Klub 99 is governed as much by generational hatred as it is an obsession with exclusivity. Perhaps a reflection of Czechoslovakia’s communist rule before its dissolution in 1993, there is an emphasis on the old social order of Klub 99 subduing, dominating, and even absorbing the younger generations into their ranks to maintain order and keep themselves in power. Gregory felt these sociopolitical shock waves in his own relationship with Mira, as he had insisted on taking her to the other side of the Iron Curtain when he moved to London. The powers that be put a stop to this planned migration, which is further hammered home by the film’s references to butterflies that are unable to fly away no matter how beautiful their wings are.

Compelling political and societal themes aside, Short Night of Glass Dolls is also just a damn good thriller (with a damn good score by legendary composer Ennio Morricone). While it has a lot on its mind, it never gets too preachy or bogged down in its own messages. Lado keeps things moving along quickly and scarily, cranking up the paranoia dial the further Gregory gets in his investigation and his journey through the morgue, to the point where what started as a political thriller is a full-on fever dream by the final act.

And what a final bow it is. Coming full circle, there’s no time to breathe as a still fully aware Gregory is prepared for his autopsy in front of an assembled audience of doctors in training. And therein lies the horror. This crime is not committed by one black-gloved killer in the shadows, it’s done by a white-gloved doctor under the bright lights of a lecture hall with a crowd of unwitting observers. But then again, the same type of brazen exposure could be said for xenophobia, generational bias, and political persecution in real life. In that way Lado comes full circle, striking one final message into the hearts of viewers, even as we watch the doctor’s knife poised above Gregory’s own heart, hoping that somehow Gregory can wake up before the blade finds its target.

---------

Keep an eye on our online hub throughout October for more of our Gialloween retrospectives!

NSFW trailer: