Last year for Indie Horror Month, I had the pleasure of diving into the history of the cult classic studio New World Pictures. It was such a blast peeking behind the curtain of low-budget genre production in the ’70s and ’80s that I figured it would be fun to go back in time a little further and explore American International Pictures, a studio that set the standard in the mid-20th century for churning out cheap, profitable, and often truly memorable films across a variety of genres.

Founded as American Releasing Corporation by James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff, the duo quickly changed the name when their first choice, AIP, became available. With principal producers Roger Corman (who would later go on to cofound the aforementioned New World Pictures) and Alex Gordon, AIP completely changed the framework for how to produce low-budget movies.

First, they monetized Peter Pan Syndrome by focusing on teenage boys as ground zero for pop culture trends under the assumption that younger audiences and girls would follow the tastes of teenage boys but not the other way around (I leave it to someone smarter than me to explore whether this was a sexist assumption on behalf of AIP, or a correct assumption based on sexist social dynamics of the time). To get ahead of these trends, AIP actually invented the concept of a focus group to gather intel on what teenage boys wanted out of their movies. With this in mind, AIP would often get the ball rolling on a production with nothing more than a title and a poster, relying on their ability to sell an idea to get it funded before getting even one word written for a screenplay.

After an initial batch of films that included westerns, crime dramas, and sci-fi, AIP took their first proper dive into horror with the 1956 film The She-Creature. Directed by Edward L. Cahn, who would go on to direct almost a dozen films for AIP in the late ’50s, The She-Creature is a prime example of the ARKOFF formula (Action, Revolution, Killing, Oratory, Fantasy, and Fornication) at work.

You get plenty of Action with gunfights and scraps against the titular She-Creature, whose existence relies on a healthy dose of Revolution as the premise hinges on the novel, if highly unlikely, idea that the creature can manifest by hypnotizing a woman to regress back to a previous life from millions of years ago. Killing is abundant as characters are frequently mauled to death by the creature in between long stretches of Oratory in the form of some world-class monologuing from the film’s nefarious hypnotist. There’s a few splashes of Fantasy as much of the film relies on pseudo-supernatural occurrences, and as for Fornication? Well, let’s just say that it likely wasn’t an accident that the She-Creature is endowed with more than just a big pair of claws.

Not only did AIP have a winning formula for producing films, they also cracked the code for maximizing profits. Rather than sell their films to bigger studios for a flat fee to serve as B-movies, they would simply produce and distribute two low-budget films and bill them as their own double feature, reaping all the profits for themselves. They also knew how to milk a winning formula, as basic plot elements from box office success I Was a Teenage Werewolf would be repackaged for follow-ups I Was a Teenage Frankenstein and Blood of Dracula.

Funnily enough, AIP’s success almost proved to be their undoing as other studios started replicating their business model. As the market became saturated, AIP started bleeding money and had to all but shut down production, sticking to distributing foreign-made films to keep making some coin while they regrouped and figured out their next move. The silver lining for fans of Italian horror is that this period gave the U.S. our first taste of Mario Bava as AIP distributed his debut feature, Black Sunday, for American audiences.

But just when things appeared to be at their darkest for AIP, salvation would swoop in, riding the wings of a raven and waving the banner of public domain, as Roger Corman realized that he could leverage some name recognition by adapting the works of Edgar Alan Poe without having to pay any royalties. In 1960 he teamed up with Vincent Price (who would star in all but one of the Poe series) to produce House of Usher. Corman pushed for and got a bigger budget, shooting the movie in color and utilizing some impressive production design. Of course, AIP made a meal out of it, plastering “In Cinemascope and Color” right in the middle of the film’s poster.

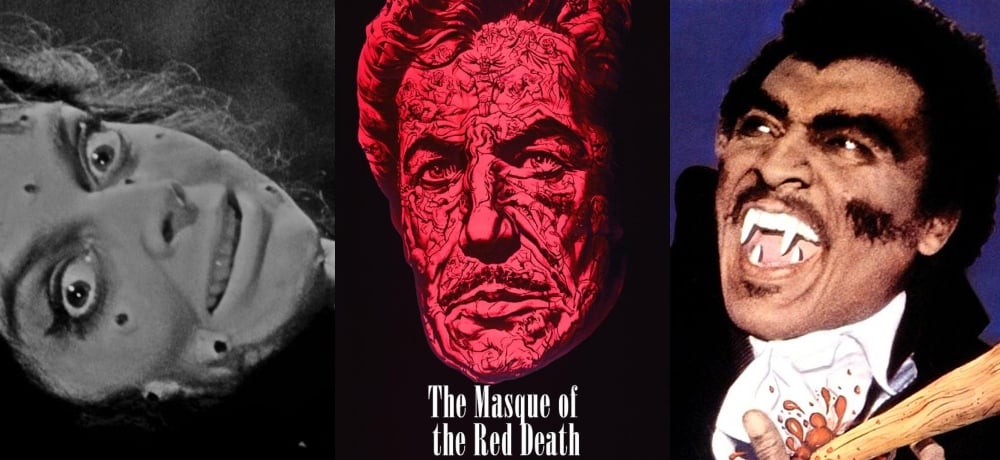

House of Usher went on to earn almost five times its $300k budget, and AIP would spend the next four years wringing as much as they could out of Poe adaptations, recycling sets and effects for subsequent films. But the films never got stale, as Corman would employ different tones in various adaptations, and Price had that special knack for playing variations of himself that never got repetitive. His blond-haired emo boy Roderick Usher, for instance, is a far cry from the mustache-twirling Prospero from 1963’s Masque of the Red Death.

Anchored by the success of the Poe series, the 1960s proved to be a decade of expansion, both in terms of creative output and in AIP’s business ventures. On the filmography side, the studio began branching out into new territory that included a wave of beach party films featuring singer Frankie Avalon and Mouseketeer Annette Fuicello, a pack of motorcycle films with stars like Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, and even a commune of psychedelic hippie flicks, some of which featured an up-and-coming Jack Nicholson.

On the business side of the house, AIP started sticking its fingers into as many pies as possible, expanding their international footprint to begin producing rather than just distributing films from outside the States, and launching both AIP-TV and AIP-Records. To keep up the capital needed for these ventures, AIP went public with 300,000 shares in 1969.

Alas, that stock may not have been the wisest investment, as the ’70s marked the beginning of the end for AIP, although they still had some gems to give the world in their final decade as an independent studio. Although one of its founders would leave as James Nicholson retired in 1972, Arkoff still had some tricks up his sleeve as he took sole control of the company.

In particular, AIP got out in front of one of the more intriguing subgenres to come out of the early ‘70s. As Ashlee Blackwell notes in her tribute to the studio, AIP became the “premiere film company for producing blaxploitation [horror] films, gaining not only a timely progressive youth audience, but the overall Black American film goer.” While the gimmicky, grindhouse essence of these films did accentuate the stereotypes already plaguing on-screen representation of Black people, they also gave Black creatives a voice not typically seen at the time.

It was during this era that Pam Grier became a household name as most of her output was with AIP in the early ’70s, including her breakout performance in Coffy. As the titular vigilante, Grier puts on an absolute clinic in a performance that breaks the mold with a character who is nuanced in ways that were unheard of in similar grindhouse fare of the era.

And of course, horror was a big part of AIP’s blaxploitation output. Now, the casual viewer would see these as nothing more than blatant rip-offs of mainstream films. And to a certain extent they most certainly were. Low-budget genre god William Girdler’s 1974 film Abby, for example, was released for all of five minutes before Warner Bros. sued for its similarities to The Exorcist. And those who know the title Blacula only by name might be forgiven for assuming it was a cheap cash grab.

But dismissing these films simply as rip-offs dismisses the importance of telling the stories from Black perspectives. Abby explores religious iconography from Black cultures that were just not visible in mainstream movies, and Blacula took things a step further by putting a Black man in the director’s chair as William Crain took what could have just been a silly gimmick and incorporated discussions of race (Dracula is racist as hell in this movie) without losing sight of the goal of spinning an entertaining vampire yarn.

After years of success in niche markets, AIP attempted to generate more widely accessible productions in the mid ’70s, a move that would ultimately be their undoing. With films such as The Amityville Horror, AIP did have some financial success, but not enough to offset the films’ increased budgets. The consequences of the failed gamble were swift, as AIP was bought out in 1980 to become a subsidiary of Filmways, Inc. Before the sale, however, AIP did give American audiences one hell of a parting gift, as their final distribution in 1979 was a little Ozploitation flick known as Mad Max.

As is the case with many independent studios that get sold to larger companies, AIP has lived in studio limbo ever since its sale in 1980. It’s currently owned by MGM, and although there was a brief relaunch in 2020, the subsequent sale of MGM to Amazon once again relegated AIP back into the cinematic ether. But while we may never see a full-blown American International Pictures renaissance, their legacy endures as a studio that spent three decades thriving and showing future filmmakers with more talent and ambition than money how they could still make it happen.

---------

Go HERE to catch up on all of our Indie Horror Month 2022 features!