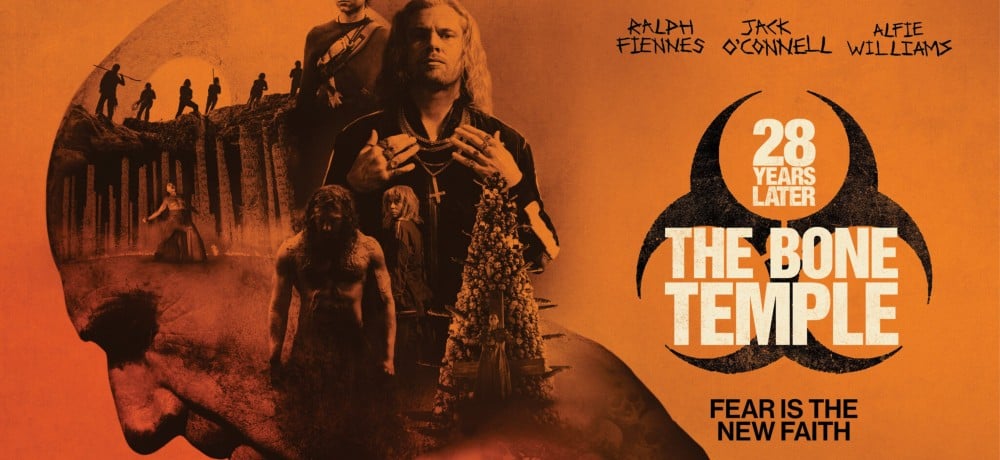

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple is about as crowd-pleasing as a horror movie gets. Filmmaker Nia DaCosta (Hedda) delivers a sequel both visceral and thought-provoking. In post-apocalyptic England, DaCosta finds humanity and fun – enriching the terrors of the world created by Alex Garland and Danny Boyle.

In short, it’s a full package of a movie with a little bit of everything, including dancing and a touching love story of sorts between Dr. Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes) and the Alpha (Chi Lewis-Parry). At the center of the film, though, is a battle of ideologies — Kelson versus Jimmy, played with a giddy ferociousness by Jack O’Connell (Sinners). It’s not just good vs. evil—it’s science vs. belief. In Alex Garland’s universe, it’s a far greater battle than man and infected.

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple kicks off the year with a blood-soaked bang, and at Daily Dead, we’re pleased to present a conversation with Nia DaCosta and Jack O’Connell about creating Jimmy’s world of control. Side note: Hearing Jack O’Connell simply say “SATAN” while looking you dead in the eyes? Wonderful.

[Editor's Note: Spoiler warning for those that haven't seen the film. Major themes and plot points are discussed.]

Nia, did you consider it a badge of honor when the Motion Picture Association saw the cut and suggested pulling back?

DaCosta: Yes. Honestly, inside of the process, we were like, Oh gosh, what are we going to do? But now that we're through and we have our R, it does make you feel proud. I was like, wow, I really shook them up. So much can be said about the process, and it's always in the press about it, but actually, they're kind of a great organization. It was very straightforward.

The intensity, as well as the borderline slapstick moments, really screams Indonesian and South Korean horror. Are those influences for you?

DaCosta: It’s the mix of tones. When I get asked about why I want to be a filmmaker, I always talk about New American 1970s cinema, blah, blah, blah. The other thing that happened, my second wave of interest and love in film, was discovering Korean cinema and the OGs – Park Chan-wook, Bong-Joon ho, all those people, their work. I was like, This is a very specific sort of cultural style. Even though they're all completely different, a lot of the commonality is that tonal mix, and I was really drawn to that. And so on this film, I got the opportunity to do that in such an extreme way.

Jack, your performance embodies those extremes. Jimmy is this dangerous yet clownfish figure. Did you see him as funny?

O'Connell: On paper there was comedy to him, for sure. I wanted to earn those moments. I didn't want to cross the line into just comedy for comedy's sake. There were plenty of clues within the writing and then the physicality of him as well. But just reveling in the sheer depravity was the main steerage for me.

Jimmy’s control of word salad is a part of his depravity, his humor. Did any cult leaders or politicians influence him?

DaCosta: We talked a little bit about cults, but not in terms of, This is who you're imitating. I feel like you did something wholly original. You did send me that picture though – that devil image.

O’Connell: It was from a satanic cult depiction of Satan.

DaCosta: The goat Satan, basically.

O'Connell: With hooves. Yeah, he was doing this with his hand [raising two fingers].

DaCosta: I love when we shot and you did that for the first time. I thought, He does his research.

O'Connell: [Laughs] Satan was my influence.

How much is the body language you created for Jimmy influenced by, not only images such as that one, but when you’re on the set with Nia and surrounded by all the elements of chaos?

O'Connell: No, it’s costumes and jewelry, things like that. Developing this personality is what I love about what we do. Yeah, just being guided by the elements then on the day. You can do your prep, but nothing will inform you better than being in the here and now.

Did you both talk a lot about how sincere Jimmy is? How much does he believe in what he says?

O'Connell: Phantasms. Phantasms. Am I saying that right? Phantasms.

DaCosta: Yeah.

O'Connell: They're phantasms, aren't they, of demonic communication? Joan of Arc, yeah.

DaCosta: It doesn't matter if she was really hearing God or not. She believes it and other people believe it. It doesn't matter if she was like, "Maybe she was epileptic, maybe this.”

I never felt like we were like, "And this is exactly what's wrong with him or this is exactly what's happening." It's more like, no, we're in a situation where this is the belief system because that's dogma, that's religion. What matters is that there's belief there.

O'Connell: And it is used to manipulate people to sway their thinking into what he wants. It is deeply bastardized.

Both Hedda and The Bone Temple explore the horror of control. Nia, what draws your work to that theme?

DaCosta: I feel so much of what makes us do the things we do is trying to maintain control, even though that's impossible because life is chaos. But it's really funny watching people try to be in control of stuff. Sometimes it's terrifying. Mostly it's terrifying. Basically, I like making movies about people who have not examined their lives at all. [Laughs]

You're very good at making fun, sad films or fun tragedies.

DaCosta: I love that. Well, because we're all so silly, you can lean into the silliness of human emotion as extreme as it gets. Life can be tragic, but also, we have so many modes and they all exist at once. Sometimes in film, they can feel like we're just going to do this mode, but that's not really true to life.

O'Connell: No, it's chaos, isn't it?

A scene that really brings that together is when the Satanist and the doctor come together for the first time. It's such an Alex Garland moment.

DaCosta: I’m a Satanist, you're an atheist.

Jack, of course it’s the meeting between Jimmy and the good doctor, but what was the bigger story you wanted to help tell there?

O'Connell: It is a trusting process type of situation. For me, that moment was representing… There’s this figure who represents utter depravity and a breakdown of any common law or social contract, who only deals in torture and pain and exploiting this apocalypse to suit him. On the other hand, you have Dr. Kelson, who is exploring it from a place of academia and trying to understand what the cure is. The advancement of the human mind against the total degeneration of it was what that scene meant for me. And then you kind of go, okay, well, that's profound. Let's lock into that.

Alex Garland often writes about the beauty and the terror of evolution. Nia, what conversations did Alex have about what this chapter meant to him? How’d you want to express those ideas visually?

DaCosta: I’ve known Alex for a few years, so we talk about this stuff just hanging out. [Laughs] One of the most gratifying things I hear from people who know me and love me and who are friends is when they watch a movie of mine and go, "Oh, that was so you." And when I read that script, I was like, "Man, this is so Alex." And that's why I also really latch onto the beautiful parts of it and the humanist parts of it.

I like to talk about that stuff anyway. With him in particular, translating it to screen, it was very much me being like: "Here's what I'm thinking. Am I on the right track? Here's how I want to maybe shift or expand or minimize." [It was those kinds of] creative conversations. And again, him and Danny, they were both so generous. They were really generous like, "Okay, this is what you're feeling. Follow that. "

Is there a particular scene in this movie that just screams your interests and just represents the cinema you want to make?

DaCosta: Maybe [Iron Maiden’s] “The Number of the Beast” [sequence]. I don't know if you get much more maximalist than that. [Laughs] What a gift that scene was.

It’s spectacular. Jack, it’s almost endearing how much Jimmy gets into Dr. Kelson’s show. What was your reaction reading it, and how did you want to play it?

O'Connell: Firstly, you think: What about this sound system that he's managed to put together? You can only imagine, can't you, not having heard music for the longest time. It's going to knock your block off, isn't it? It's heavy metal, so it's going to really hit.

Nia, where did your mind first go in visualizing that sequence?

DaCosta: Oh my God. I literally read it on the page and I was like mhmm, and then mind blank. Who knows? And then the thing is, trusting the process, you get drawn to certain elements. Okay, I want this for the Jimmies – it’s the first time some of them are hearing projected music. And like you're saying for [Jack's] character, it's the first time in a long time hearing that kind of projected music.

O'Connell: For the youngsters, yeah, never seen it. The first time ever.

DaCosta: So I wanted this to be like they're at a concert and their first time moshing. I want that energy. I also wanted to mix into ecstatic dance. You know, ecstatic Indian dance?

I don’t, no.

DaCosta: Ecstasy, technically, is about connection to God or a higher power. And so, I want it to be ecstatic in that god-like way.

And then the ring of fire came into it. My production designers were hugely influential on this process as well, Gareth [Pugh] and Carson [McColl]. They're brilliant. These were their first films, the 28 Years Later films. They come from fashion and live events and live performance. It was just like, okay, here's an element we think is cool. Boom. Otto, the sparkle staff, fire guy, element we think is cool, boom, put it in, ring a fire, boom, put it in.

And then it's like, can we make this all work together and have a flow and can we create something that makes the Jimmys react in the way that they do, including this guy, who knows it's not real, but he’s still enraptured by it.

Very childlike enthusiasm, which makes you wonder, is Jimmy not that different from the boy we were introduced to in 28 Years Later?

O'Connell: Totally. I don't think he was emotionally intelligent at all. There's a sociopathic nature to him. I don't think he has developed socially whatsoever, but he survived and they're efficient at what they do. I was led by both of those theories, really.

What's key about that is that we have to believe that they are very proficient at what they do. If we fail to do that, that'd be flawed. Seeing them dispatch infected folks with ease — that was important.

Nia, as you said, the production designers come from live events. Metal is a definite influence there, of course, but what else is in the melting pot of influences for Bone Temple? Any pieces of art, music, or literature that inspired you?

O'Connell: Satan. For me, Satan.

DaCosta: A lot of cults, because I didn't want them to feel like a gang. They needed to feel like a cult – a cult of personality. “You have blonde hair. We're going to have a blonde wig."

O'Connell: You said Joan of Arc. I bought a Joan of Arc book and read it. It was months prior to the shoot. I am genuinely glad I did.

DaCosta: That's why I love working with Jack. You research. I love research.

O'Connell: Geek.

DaCosta: And that's also part of making films. It was so fun. It's like being back in school, you get a topic and you're like, I'm going to dive into this and be an expert for six months. Joan of Arc was huge for me in understanding Jimmy, though.

But I tend not to, visually, I try not to reference other films because you're going to do that naturally anyway because you've seen them, whatever. I try to do paintings a lot of the time. In the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid, there's a section where it's all abstract art. I was like, that's basically this Jimmy's. I don't know why. [Laughs]

The blood, the fire, and nature – it’s all so lush, the fire. What were your first conversations with [cinematographer] Sean [Bobbitt] about what you two wanted to achieve with the Bone Temple?

DaCosta: I wanted the Bone Temple and Kelson's world to be beautiful, measured. Actually, film-wise, I’m influenced by Barry Lyndon a lot, especially the way Kubrick shoots those exteriors and how he clearly is referencing Baroque paintings in certain scenes. And so, we talked about that.

When I have someone like Sean shooting the film, and I have someone like Tom Poole doing the coloring, I'm like, We're going to be fine. I can just say whatever's coming to my head, and then Sean's like, "Oh, you're saying this, this, and this." I'm like, "Yeah, bro." And then Tom's like, boop, boop, boop. Then he makes this amazing LUT.

It's just… I don't know. I don't know, man. It's just vibing out [Laughs].

It grows naturally.

DaCosta: Yeah, because everything for me comes from character and theme, and that's what leads to the visuals. And so, it was just us coming to the same understanding about what the arcs were and what the themes were.