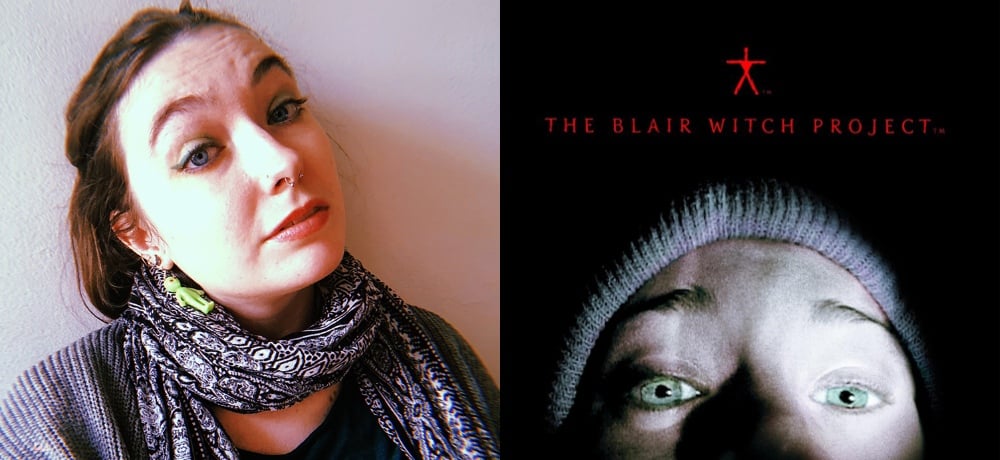

Welcome back to Let’s Scare Bryan to Death, where we’re joined by horror critic and academic Mary Beth McAndrews. You’ve likely read her stuff at, well, a sh*tload of outlets, including Grim Journal, Rue Morgue, We Are Horror, Film School Rejects, and Shudder’s The Bite (check out the full list at her website). You’ve probably also heard her voice on podcasts Scarred for Life, where she and previous guest Terry Mesnard discuss the movies that messed us up as kids and Watched Once, Never Again, where she and Dax Ebaben discuss the movies that mess us up regardless of our age.

It’s also no coincidence that you’ll find McAndrews as a contributor in House of Leaves’ upcoming book Filtered Reality: The Progenitors and Evolution of Found Footage Horror. She is an avid champion of the found footage subgenre, and for this month’s movie she picked a pioneer of the format, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez’s The Blair Witch Project.

I’m pretty thrilled at the opportunity to discuss this movie for two reasons. First, as usual, this is a glaring oversight that I’m happy to correct. Second, as someone who hates coming up with synopses, this is likely to be the easiest one I’ll ever need to write: three members of a documentary crew (Heather Donahue, Joshua Leonard, and Michael Williams using their real names for their characters) travel into the woods near Burkittsville, Maryland, in search of the fabled Blair Witch and soon find themselves lost and stalked by the enigmatic entity.

Of course, the premise isn’t what makes The Blair Witch Project such a noteworthy film. This movie was a phenomenon at the turn of the millennium, turning a $500k budget into over $280 million at the box office with a blend of creative filmmaking and one hell of a marketing campaign that convinced a lot of people that what they were seeing was real. It definitely left an impression on McAndrews the first time she watched it.

This is a movie that my dad had been talking about for a long time. I think I was 11 or 12 when I saw it, and [the event] is burned into my head. I even remember the layout of the living room, with the pink armchairs, the coffee table, the couch, and the front door in [my dad’s] apartment. I watched it, I was silent the whole time, and then as soon as the movie was over, I threw a pillow at my dad and almost started crying because it was so scary. He had never seen me that scared before, and he'd shown me a lot of scary movies. His wife at the time was a server, so he would leave me at home while he went to pick her up. This time I would not let him leave me home alone. I had to go with him to pick her up from work, and she was like, “Why is she in the car?” And my dad said, “We watched The Blair Witch Project.”

My dad had talked about it, and I’d heard people talking about it saying, “Oh, it was the scariest thing I’ve ever seen, I thought it was real!” So I knew that it wasn’t real, but it was also the first found footage movie I’d ever seen, so I was confused. I was like, “Is this kind of real? Is this not all the way real?” I was very confused about that. But I also went to Girl Scout camp every summer in Maryland. Not in Burkittsville, Maryland, in a very different part of Maryland. But in my head all the woods in Maryland were the exact same thing, despite one being in the north part of the state and the other being in the west part of the state. I was terrified to go to summer camp that year, terrified to be out there at night, to have to deal with the woods. Terrifying. And the camp I went to had one of those lone, brick fireplaces in the middle of a field, so it was always this urban legend and I was convinced that the Blair Witch was hiding in the chimney. That’s all to say that I knew it wasn’t real, but my brain still had a hard time parsing out what it was. I had never seen a movie like it before.

Despite being terrified, McAndrews was hooked on the found footage format. She’s drawn to the creativity and experimentation inherent to the subgenre, and she thinks it gets an unwarranted bad rap among horror fans.

I think sometimes it's just en vogue to say that found footage is sh*tty and be like, “Oh, The Blair Witch Project isn't that good, or this isn’t that good of a movie.” There are so many cool movies out there that are so different from those films, but also The Blair Witch Project is a very important movie in the history of horror cinema, and cinema in general. No one was doing that kind of thing, the way they innovated low-budget filmmaking. And then Paranormal Activity changed the game, so did Cloverfield. But people want to dunk on these movies, and if you don't like them, you don't like them. That's totally fine, but you can't deny their artistic merit and what they have led to in the horror genre in terms of filmmaking, both in terms of found footage movies, but also in non-found footage movies. The Invisible Man, for example, took cues from Paranormal Activity with some of those long, static shots that made you really look around the screen. Those found footage techniques are being used in non-found footage films and they're really, really effective.

McAndrews counters the dismissals that “nothing actually happens in the film” by pointing out that the film’s restraint is precisely what makes it so effective. It’s willing to make the audience sit in the dread of the moment, as is the case with a lot of the great found footage films.

Most movies don't do the long static shots unless they’re an artsier movie. I feel like Paranormal Activity has just enough justification for those long, static shots, as does The Blair Witch Project. Like at the end when Josh is stuck in the corner, and the camera’s just on him and you’re waiting for something to jump out. That is “chef’s kiss” found footage where nothing happens, but you are about to throw up because you're so tense as you're waiting for something to jump out. And your eyes are just scanning the screen, and that is what is so cool about found footage and that way of building tension.

Having just seen it myself, I can confirm that 20-plus years after its release it’s still a pretty potent experience, which as McAndrews notes is due in large part to its ability to immerse the viewer in the action, while also asking us to be in for the ride.

The viewer needs to be participating in it. That's an important part of found footage. If you aren't actively trying to be a part of the film and you're only half paying attention, you're not going to get it. And I think that happens a lot with The Blair Witch Project because a lot of the scares are sound-based or tension-based. Like I said, in some cases nothing happens because there are no effects... but I also just think that it's an amazing example of how to build tension both with a potentially supernatural force and between people. Those two conflicts come together to create this perfect storm of absolute confusion and terror. I think it doesn't help that I'm already terrified of the woods, and I think the woods are one spooky f*cking place. Just the concept in general of being lost in the woods and not being able to get out to me is terrifying. This could happen, in my head it seems very much like something that could ostensibly happen if you take out the idea of the witch.

The movie also tackles the question that always seems to pop up regarding found footage films: why are these people still recording these events rather than focusing on things like not dying? As the situation for the trio becomes more dire, there’s a brief interlude where Josh acknowledges that the cameras serve as something of a mental shield by adding a layer of artifice to a situation that’s becoming all too real. It’s a sentiment that’s stuck with McAndrews years later.

I do video work for my day job and whenever I'm filming something, I think about that line. Isn't it like the cheesiest thing? I literally think about that part in The Blair Witch Project where it's like, “You're seeing a mediated version of reality when you're in reality.” It's so trippy and weird, but you're watching your reality through a screen, and it really does seem like you're not seeing what's in front of you. It's just so bizarre and it captures that feeling really well in that line. Even though I'm filming dogs doing cute stuff, so it's not as terrifying, obviously, but that kind of conceit still rings true.

There’s also an element of the production that adds a layer of veracity to the film, for better or worse. Donahue, Leonard, and Williams were cast because of their improvisational skills, and Leonard was in part cast because he knew how to work a camera. The movie wasn’t filmed as a series of shots, but rather the group was left in the woods with notes left in their gear each morning about what was supposed to happen over the course of that day. The production crew then proceeded to torment the trio over the course of eight days to elicit the agitation and fear seen on camera. And as McAndrews states, much of what we’re seeing isn’t strictly acting, as both Leonard and Williams started to turn on Donahue.

Heather is like the director of the movie, and the two guys start antagonizing her. And that was real. They were f*cking with her and antagonizing her, not just in character, but as people. So those feelings of her on camera is one of those things where it might be acted, it might be real. There was a kind of unethical blurring of boundaries there to create these real relationships and interactions between them. They also got super f*cked afterward because they had to lay low and pretend they were dead. They actually had to disappear.

So in a sense, while we’re not seeing these people actually die, it’s still disturbing to see what they’re going through, especially considering how, as McAndrews explains, the fees the actors were paid didn’t account for how much money the movie would eventually go on to make. The ethics (or lack thereof) definitely add an icky vibe, but also add to the lore of the overall experience.

Seen on film, these real-life tensions land so well because the supernatural threat of the Blair Witch remains in the background, casting a pall over the group without ever actually being seen. And for McAndrews, relegating the witch to our collective imaginations keeps her that much more terrifying.

Every time I watch this movie there's that scene where Heather's looking to her left and going, “What the f*ck is that, what the f*ck is that?” And all my life I've always wanted to know what it is. But if I knew what she was looking at, then it wouldn't be such a memorable moment to me. It makes it all the more terrifying where if you think about it, she's running, she's terrified, and she can't quite get her camera to capture what it is. That's not on her list of priorities, because that sure as sh*t wouldn't be on my list of priorities. In Blair Witch (2016) by Adam Wingard, they did show what the Blair Witch was, very briefly, and everyone was very frustrated. I thought it was cool, but that's the thing. You get these people who are like, “That's a stupid looking monster.” So if you don't have it in there, it's your imagination.

Ultimately, McAndrews believes that history will be kind to The Blair Witch Project as people continue connecting the dots to how it has shaped the genre for the better.

The Blair Witch Project’s legacy to me is that it isn’t the birth mother, but maybe the fairy godmother of found footage movies. It is not the first, and it certainly is not the last, but it’s like this beacon of light for this new way of making horror films. Films like The Last Broadcast, Ghostwatch, and Cannibal Holocaust came before The Blair Witch Project, but there's something about this that is so special. It ignited a whole new movement in genre filmmaking that is still going strong today. I’ve been seeing found footage becoming more popular, and I think there's going to be a newfound appreciation for The Blair Witch Project, not only in its craft, but also how it's influenced and inspired countless other horror filmmakers to go out into their backyards with a camera. Shoot that weird movie you want. It doesn't matter if you have the backing of a studio, you can still make something really good.

Indeed, creators are pushing to the found footage format to thrive on new platforms, really experimenting with methods we tell stories. And as McAndrews explains, it all goes back to those poor three filmmakers in Burkittsville, Maryland.

Now there's this really cool realm of found footage coming up on TikTok that's really cool. People are filming... they're either going ghost hunting or someone is creating an entire narrative about something following them, but it's really cool on TikTok because it's harder to tell if this is an actual experience or is someone creating a production to make it look like found footage? There is a super cool, blurred line about what is happening now on TikTok with these super short clips, and it's really interesting to think about [the trajectory] from The Blair Witch Project to this and what technology has done to shape what we think is real in horror.

[Found footage] adapts to technological advances in filmmaking, but also it is very reflective in that it makes us question how we watch horror movies, how we experience horror movies, and our relationship to what it means for something to be true versus manipulating the truth. I think The Blair Witch Project, not just the film, but also the entire zeitgeist and cultural thing around the film, is a huge testament to the amount of trust we can put in filmmakers when they label something a certain way. And the power that comes with that trust, and how we can be so manipulated by that. I think that manipulation of truth in tandem with these technological advances that are used in these films make found footage such a fascinating subgenre of filmmaking that deserves way more attention and love than it gets.