A mere few years ago, the notion that a subgenre as strange and specific as folk horror becoming overexposed seemed unlikely. But with the one-two punch of Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2016) and Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019) – films that brought more modern concerns surrounding gender dynamics and romantic/familial relationships into the genre – and the work and dedication of film scholar Kier-La Janisse (whose 2021 documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror might well be the final word on the subject), stories of pagan cult sacrifice and shape-shifting bog witches have become practically mainstream in a world as technologically detached from its primeval roots as its ever been. Enter Starve Acre, an adaptation of the book by Andrew Michael Hurley which started as a bogus “lost novel” supposedly written in 1972 and originally published by Dead Ink Books attributed to a “Jonathan Buckley.” Hurley himself has been a force in the Folk Horror revival abroad with his novels The Lonely and Devil’s Day, and though Daniel Kokotajlo’s screen adaptation of Starve Acre is summarily familiar and uninventive, it manages to tap into the same old-fangled, ambiguous creepitude that made Hurley’s mysterious book so popular.

Having returned to the Yorkshire of his youth, archaeologist Richard (Matt Smith) spends his days knee deep in pits, fiddling with bones while his wife Juliette (Morfydd Clark), cares for their sickly son, Owen who seems to hear voice of Jack Grey, a local myth that has haunted Richard since his own childhood. After Owen takes ill and passes away, Richard and Juliette’s marriage is expectedly shaken, but when visit from a medium leads to supernatural occurrences, including a skeletal hare reconstituting itself, grief turns to obsession as the couple are soon touched by the malevolent forces buried in the soil that their fractured home is built upon.

The Yorkshire Dales do a lot of atmospheric heavy lifting here, but the nerve-mangling score by Matthew Herbert lifts things to an entirely different plane. Building from delicate music box leitmotifs to a soaring, near-psychedelic intensity, Herbert’s soundscape nearly overwhelms everything else, which is okay as the plot is conspicuously thin. Kokotajlo’s screen treatment of Hurley’s already enigmatic novel is even more vague, and, after a leisurely first hour, the storytelling tumbles off a muddy escarpment. The extended climax offers both too much and too little; big reveals blow over like thunderheads and it feels as if whatever story the actors are trying to tell can find no purchase in the garbled visual and aural din.

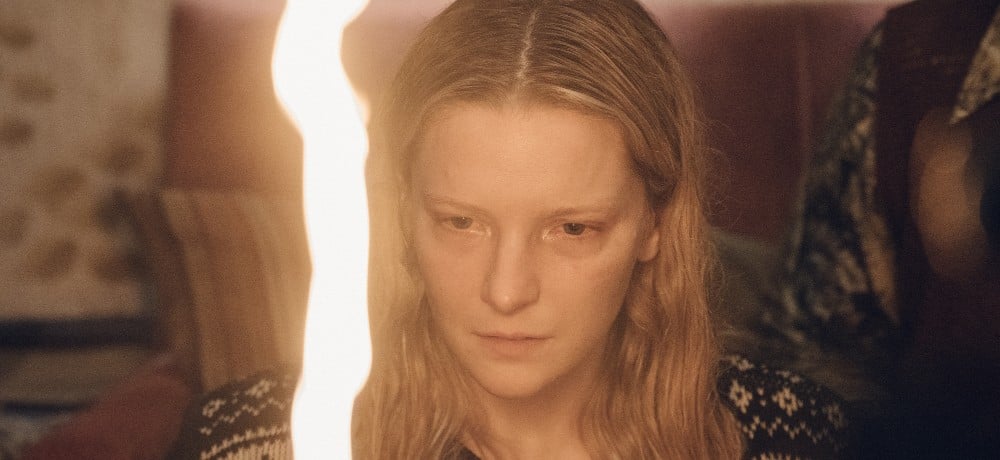

Luckily, Smith and Clark are compelling even when it’s difficult to parse what’s going on, and though the material doesn’t give them too much to do beyond blank-eyed moping and sobs, they both play the grief they share with such skill that Starve Acre acquires shades of such gloomy ‘70s parapsychological dead kid pics as Audrey Rose and Don’t Look Now. It may have no chance of standing alongside those classics, but Smith broods as if born to it and Clark’s face continues to be an invaluable tool for conjuring the sort of transcendent misery she so effectively portrayed in Saint Maud. Also worth noting: the film’s third lead, the revivified hare so prominently displayed on the marketing materials and very successfully realized with the aid of a handful of puppeteers and SFX, has nearly as much presence as its human co-stars.

Though obviously indebted to the folk horror novels and cinema that came before it, Starve Acre wears its derivations on its moss-caked sleeve, presenting a tale of buried secrets and pagan rites with no concern for subversion or contemporary relevance. Though if feels as if Kokotajlo loses control of his material in the last act, the film’s overwhelming atmosphere of unknowable, ancient dread is hard to resist, and its final tableau lingers in the mind like the roots of a tree long since cut down that continue to reach inextricably deep.

Movie Score: 3/5