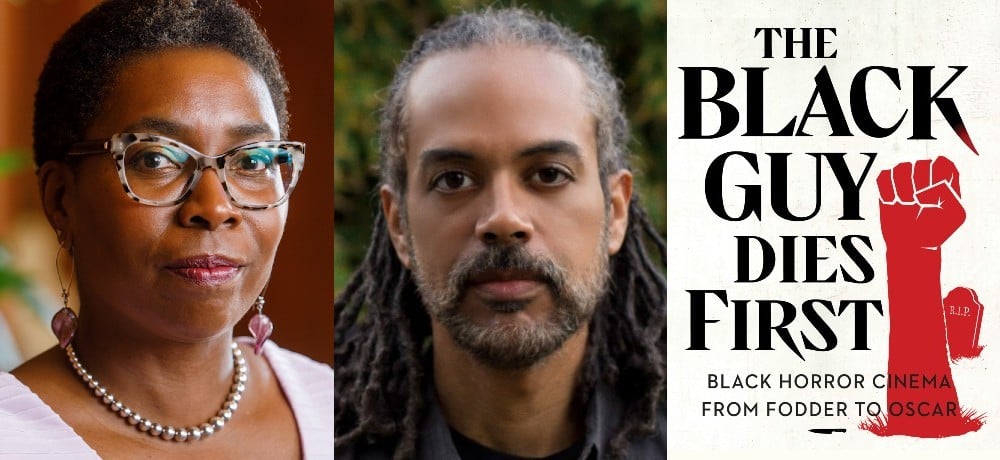

Diving deeper into the world of Black horror, The Black Guy Dies First: Black Horror Cinema from Fodder to Oscar co-authored by Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman and Mark H. Harris, takes a deep exploration into the Black image in modern horror cinema and how that image reflects and impacts the Black American experience.

Coleman is the author of the foremost guide for Black horror cinema Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present. This was the inspiration and base for the Shudder documentary Horror Noire where she was featured as an on-screen expert and executive producer. At Northwestern University, she is the Vice President & Associate Provost for Diversity and Inclusion. Coleman is also an award-winning scholar who specializes in the cultural politics of Blackness and media studies.

Harris, who was also featured as an onscreen in the Horror Noire documentary, is a Black horror authority. For over twenty years, he’s written about cinema and pop culture as an entertainment journalist, with his work featured in several outlets including New York magazine and Vulture. In 2005, Harris started and continues to run BlackHorrorMovies.com, the foremost online source documenting Black horror cinema, from its history to contemporary representation and accomplishments.

In our interview, Coleman and Harris share what started their passions for horror, the significance of 1968, the evolution of persistent stereotypes, and what they hope to see in the future of Black horror.

What inspired you to write your book Horror Noir?

Coleman: I've often told this story, that I believe horror, specifically Black horror is my birthright. But that I mean, I was born and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. That’s where George A. Romero developed his film chops. He went to Carnegie Mellon University. But most importantly, he filmed Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead in and around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Horror is in every Pittsburghers DNA, including mine.

How was the reaction from horror fans with the Horror Noire book?

Coleman: It was unbelievable. It truly is. I was writing two books at the same time. The first one was the history of the NAACP and their involvement in media activism. While I was writing that book, when I would take a break, because writing is hard, I would shift to writing a series of essays on the history of Black people in horror movies. When I was writing that, it was the rest. It was joyful. That doesn't mean that the NAACP isn't important. But this was really developing.

Very few of my colleagues said, “Go forward with horror.” People were concerned. They were skeptical. I'm a tenured professor, and they were asking, “Really? Is that where you want to go next?” So, I've been slowly chipping away at the NAACP book. But I went full on into Horror Noire. It was just kind of out there. And people said, “This is kind of cool.” Then, Ashley Blackwell of GraveyardShiftSisters.com said, “I can see this as a documentary. I can see this as a screenplay.”

Everything changed. The book changed the genre and gave horror filmmakers permission to do Black horror. Specifically, to call it that. So that was the first sea change when that book came out. There are filmmakers I won't name names, who said, “I've been wanting to do this. Finally!”

What was the impact of the Horror Noire documentary?

Coleman: We're talking today because Horror Noire, the documentary that streamed on Shudder. That reach was just amazing. Everything blew up. So in some ways, I feel like we’ll take some credit for a kind of catapulting Shudder, because Horror Noire did so well. It was the number one documentary on the platform. There's also a reach benefit that the documentary benefited from and was extended certainly through COVID, when people couldn't go to the theaters.

Now, Horror Noire is sort of a brand, like the way we talk about Xerox or Jell-O. Black horror movies are called Horror Noire. And that's pretty cool.

How did you become involved with entertainment journalism?

Harris: I've always loved movies, ever since I was a kid. At some point during my adolescence I developed a love for writing too. I would write little stupid stories like about killer cats. I wrote a slasher story about a middle school dance when I was about twelve or so. The love of movies and writing eventually merged and just seemed like something natural for me to do. It's not my full-time job, but it's something that I enjoy doing in my free time.

What inspired you to start your horror site BalckHorrorMovies.com?

Harris: I've always loved horror movies and have always paid attention to the role of the Black folks in horror movies and their fate. Back in the early 2000s, I decided to look to see if there's a site that's devoted to it, or any kind of articles devoted to the Black role and horror movies. I just couldn't find anything. I thought, “Hey, if there's nothing out there, I may as well do it myself.” I have a decent amount of knowledge about horror movies. I've seen a bunch of them. I've paid attention to how Black people are treated in the movies. It just went from there.

When did you gain an interest in horror?

Harris: I've always kind of had been drawn to dark storylines. The one movie that I really remember drawing me in was the original Night of the Living Dead. I remember renting a VHS copy from the library when I was probably twelve or so and just not quite sure what to expect. It really blew me away. That it was just this black and white movie and it still seemed so modern in terms of its edginess. And the fact that it had a Black hero in the story just flabbergasted me. It’s something that just seemed so ahead of its time. Even when I was watching it in the 1980s, it seemed like it would have been revolutionary at that time. It was something that really just stuck with me and helped deepen my love for the genre.

Coleman: I would point back to perhaps something even earlier in Pittsburgh. There was a news caster, his name was Bill Cordell, who largely did the weather. He had a late-night sort of thriller spooky nighttime series that was called Chilly Billy's Theater. There were a lot of Universal Monsters, classic horror films, and a lot of Godzilla films. I was very young, like five or six years old. I would stay up with my mom and we would watch Chilly Billy’s Theater.

My mom hates the story, because it sounds so peculiar, but I wrote in one of my books that we would stay up and eat heavily seasoned fried chicken livers and chocolate cake, which is still one of my favorite meals. Yes, I was that kind of kid. Between the two, I really liked the chicken livers, and she ate the chocolate cake. So, we would eat chicken livers and chocolate cake and watch Chilly Billy.

Those movies like The Invisible Man, The Mummy, Frankenstein, and all the Godzilla movies weren't particularly scary. So, it was okay for a young person. They all have these interesting moral lessons about what we're doing to the earth or each other. They had a deep effect on me.

Who are some of your favorite horror filmmakers?

Harris: Jordan Peele certainly is the obvious one in terms of Black filmmakers. He's kind of set the bar for Black horror in recent years. Expanding beyond Black filmmakers, I've always enjoyed John Carpenter and Wes Craven movies. I'm a kid of the 1980s, so I watched a lot of stuff from that era.

Coleman: I really like Kasi Lemmons’ Eve's Bayou which some will be surprised we talk about as a horror film. It's not in the same sort of sense. If we continue that line, I really like Charles Burnett's To Sleep with Anger, a sort of haunting film, like Eve's Bayou. I don't think Burnett would say that To Sleep with Anger is a horror film in the strictest sense. J. D. Dillard did Sweetheart, which I think is really interesting, along the same lines as Barbarian, where you have a Black final girl. I like that emerging trend. It's good to see women taking their taking center stage in the genre.

How did you come up with the concept for this book?

Harris: It was years in the making, in terms of Robin and I wanting to do something together. She reached out to me, probably close to 10 years ago, just touching base because we're, quote unquote, experts on the same topic. We kind of said, “Oh, wouldn’t it be nice to do something together at some point?” But we had nothing really concrete planned.

After the Horror Noire documentary came out, it had a lot of really good feedback. The folks over at Saga Press, Joe Monti, in particular, heads up Saga Press, reached out to Robin and wanted to do a follow-up to the documentary, because he saw it and loved it. He wanted to do a book that was kind of a follow-up to it. I think he wanted something that was a little more mainstream, not quite as academic as Horror Noire. He asked her to write it, and she pulled me in.

We worked together on it, and it was really fun. It was a dream project for us. It took about a year to write, but it was in the review and publication process for a year and a half now. So it's great to have it finally come out.

Coleman: I'm gonna just add that Mark makes this sound very smart, well-planned, and official. But I also just want to say that I relied very heavily on Mark's site, BlackHorrorMovies.com to write Horror Noire. I want people to know it's a public site and super accessible. But scholars who do research and anybody who's worth their salt, need to go to Mark’s site and pay attention. It's a really important film archive. I was deeply influenced by that. And absolutely, I reached out to Mark. This was a huge help for me. You'll see the humor on that site elevates The Black Guy Dies First.

In the book, 1968 is listed as a significant year in Black horror with the films Spider Baby and Night of the Living Dead. How different were the impacts of these films on the genre?

Harris: They're both really ahead of their time, in different ways. Night of the Living Dead was definitely ahead of its time, in terms of having a Black central character, who was the lead. His race wasn't actually even mentioned in the movie. He was the guy who took charge. That is something that even two decades later would have still been really revolutionary, because Black people weren't really allotted the lead roles, until like maybe the 1990s or beyond. Now, in the last 10 years or so, it really has become something that you see on a recurring basis.

I think Spider Baby was ahead of his times in terms of the backwoods horror type of thing. It's kind of a precursor to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes. It was ahead of his time in that sense. But it was also a sort of harbinger of things to come, in terms of its dismissal of its only Black character within the first five minutes of the movie. It wasn't the first movie to have the Black guy die first, but it was a template for that kind of thing, where the Black character is dismissed early on. They really don't have much to do other than to die, to establish the danger in the storyline. That is kind of a reason we chose that movie. It’s the polar opposite of Night of the Living Dead, in terms of the roles of the Black characters in each movie.

Coleman: I think we do a really good job of connecting the two with a red thread. To sort of elaborate on what Mark said, Spider Baby is interesting, because it kind of marks an end of when you have, or at least we hoped it would mark an end of senseless annihilation of Black people. Quite literally the destruction of Black bodies as represented through Mantan Moreland’s character showing up. He’s a great comedic actor, whose only role or purpose is to play the [nameless] messenger, who is included to kind of up the body count. There's something about that very perfunctory annihilation of Blackness in these horror films that we wanted to reflect on.

I think that connects to Night of the Living Dead in a very different way. A different kind of social commentary that has obviously been sparked with this movie. The way that the character Ben is super heroic and all of the things we know about that, but then his demise, his sort of lynching at the end, forces us to think about not only what's happening in the cinematic universe around the treatment of Black characters, but also for the treatment in the real. How much do we value Blackness or not? That was an important connection that we were trying to make.

The other is a reflection on color blind casting. People brag, “They were simply the best actor.” And people always only say that when a Black person shows up in a role. There's sort of a bragging around colorblind casting, and people leave it there as the sort of period. That's a comma, not a period because colorblind casting doesn't mean that we don't bring our color, our Blackness, our Brownness which is our lived experiences, histories, culture, aesthetic, vernacular music, all of that, to those performances, and the ways in which people read us.

There's another film, The Girl with All the Gifts. They said, “Oh, she was just the best actress. It was colorblind casting.” But now, there's a meaning behind the fact that you've got a little Black girl as the star, the hero, and technically the final girl. It’s a win-win. We typically don't see BIPOC folks as the final girl ever. Final girls are white typically. So I think those things are important.

Why have we seen the stereotype in a horror movie of the Black person either the first, or one of the first to die?

Harris: It's a reflection of the value that Hollywood places on Black roles or roles of color. Hollywood is a reflection of society. And Hollywood kind of thinks that the hero has to be this white paragon of virtue and stuff. And that’s the, quote, unquote, American image. It's a reflection of what has come through in society, as to what is the ideal American, or what is the ideal hero. What do they look like?

I think Hollywood has bought into that fully, and at least until the last few years, it's really reflected in horror movies specifically. If you're not the lead, then you end up dead, typically. That's definitely how it translates with the people of color in horror movies. They just end up dead or by the wayside at some point. A heroic death is actually one of the better fates for these characters a lot of times. At least they don't die in the first few minutes. That's just kind of how Hollywood has stacked the priorities in terms of who is the hero and who is not.

Coleman: I would go even a bit stronger. What Mark is talking about is, what does it mean when folks of color are destroyed in this way? Even in entertainment. Even in the imaginary. I think it's solidifying in one's imagination, a kind of investment in, I would say, white supremacy. I want to be also clear that all sorts of folks can be invested in white supremacy and that it's often white folks. But it can be anybody.

And there's sort of implicit but also tacit investments. And how does that show up? How does that investment in white supremacy show up? So, how do you mark someone as heroic? How do you mark them as superior? How do you mark them as intellectual? You could name that. But if you do that through the destruction of folks of color through the knots, that's where it flips to a kind of, I'm investing in White supremacy, right?

I love where Rachel True says in Horror Noire, “Everybody lives or everybody dies, right?” That's a rejection of that. An investment in that kind of narrative around supremacy is to say that to evidence that there is someone who is superior requires the decimation of another and that would carry their histories, their culture.

So, for example, even outside of Blackness, per se, is the annihilation of Native American and Indigenous folks, symbolically in the horror genre. What does that look like? Pet Cemetery, Amityville Horror, The Shining, Poltergeist, and Wolfen. All of these movies are about the annihilation of Indigenous folks. An annihilation of an understanding of Indigenous histories and culture. But also, blaming them for the ills of our social world and that they are the threat to whiteness. That's the classic example of an investment in white supremacy.

In the book, there's a discussion about Black tropes, and how they appear in contemporary horror, such as being sacrificial. What would you say are some of the more common tropes that still show up in contemporary horror?

Harris: That's definitely a big one that you still see quite a bit. In some ways, that's Hollywood's way to try to make Black people or people of color look better than they have in the past. So a sacrificial Negro would be someone who dies, but they do an act of heroism, as they sacrifice themselves for the white hero.

Another one would be an authority figure. In Hollywood’s mind I think they think, “Oh, it's a good character, because he's not a criminal, it's not doing anything bad.”

On the other hand, they're this flat one-dimensional character who’s like a cop, or something that's just there to impede the hero. They're not really furthering the plot or doing anything really significant.

Another similar one would be the sidekick, who's typically the Black best friend that’s there to support the white hero and goes along for the ride. They may or may not live. If they don't live, that serves to give the hero or make the story deeper in that sense. Some of the tropes are better than others, technically. But they're all still typically ways to kind of marginalize the characters of color in the storyline.

In the book, there's discussion of politics and social issue themes in horror. What do you think critics of political- driven horror misunderstand about that concept?

Harris: What did they miss? Well, where can we start? It's just exploded into a bigger societal issue in terms of people who don't want to face the ills of the past and the present. They are trying to just erase things. They want to erase history. They don't want to think that someone that they're descended from may have done something bad that may have some impact still today. I think that there's just a general effort to kind of just erase whatever makes people feel bad.

I think Black people and people of color who've learned history throughout school are kind of used to seeing these stories, where we feel bad watching these stories, or watching things happen to us throughout history. And yet now, all of a sudden, once we are to the point where we're highlighting these stories and highlighting the ills of the past, the powers that we are trying to cover it up. Now, it's making them feel bad. It's really endemic of just how politics and a lot of people in society are today, in terms of wanting to cover things up and stick their head in the sand. I'm sure Robin has encountered this a lot in the academic world herself.

Coleman: I also think that there's something just slightly even more nefarious at work, because people have called these bills, sort of white fragility laws, the anti-woke moment. And I actually don't think that there's anything fragile about what they're doing. It isn't particularly protective of them. I do think this is less about them feeling bad about engaging in these ideas and more about simply silencing everybody else. It's an erasure that I'm deeply worried about as someone who is in higher education about what's happening in K-12 education. I don't think it's confined to red states or even purple states. Its impact is now national, if not global.

We are going to have to be prepared in higher-ed for a whole generation of students who don't have the exposure or the training around critical thought. They're going to be absent from a whole curricula around history, cultural studies, religious studies, gender, and sexuality. It's opening the door for something far more dangerous, which is all anti-trans, anti-Black, anti-liberal, anti-Latinx, or Islamophobic. All of these are what comes next. It's the first step in a trajectory of state-sanctioned racism. I’m deeply concerned for this country about that.

Harris: That goes back to the heart of what “Make America Great Again” really means. Great for who? People are trying to push things back to the way things were when white people were in power and everyone else kind of just fell in line.

Coleman: Remember Rusty Cundieff in Tales from the Hood. It’s the third story in the anthology, he said, “Vote for an original American.”

Harris: Yeah, the one with the dolls.

Coleman: When you watch it now, you’re think, “Good, Lord!” This was so prescient. It sounds so much like Donald Trump’s slogan, too. It felt a little, not entirely fantastical, but a little bit fantastical.

That's also the challenge of the horror genre. What we've come up with lately has been so horrifying that it's really got to push our imagination. The January 6th capital attack, who would have imagined that? That looked just like World War Z. Now, we’ve got to go harder in the genre, because these shenanigans we're doing in real life are exceeding our imagination in horror. I mean, there was a noose and they constructed gallows. It's just unbelievable.

How has streaming impacted Black horror?

Harris: It's been great for Black horror. Even with the success of Get Out, I think there's still a reluctance on Hollywood's part to put Black-led stories in horror or in any other genre on the big screen. Streaming has been a good alternative that has allowed studios to have less risk putting something out on streaming services. It's been home to a lot of great Black-led horror movies on Netflix, Amazon Prime, or Hulu. There’s been just a ton of stuff. Hulu has the Into the Dark series of movies where more than half of them have been led by people of color, which is really astounding to me.

Ideally, we’ll get to the point where you can see more of those movies led by Black people on the big screen. But for now, at least, they’re getting out there on streaming services and not being held in some sort of limbo somewhere.

In the next few years, what direction do you see Black horror going towards?

Harris: First and foremost, I hope that it will continue because there’s no guarantee of that. Hollywood has its trends and things that it allows to happen. We’ve seen in the past, in the Blaxploitation era and in the 1990s, where we've had this surge of black movies come out and then Hollywood decides that they're done with that and want to move on to something else.

I'm hoping that it will just continue to expand and not kind of just try to replicate the success of Jordan Peele, Get Out specifically. After Get Out was so popular there were a lot of movies that wanted to go in that direction and replicate that. I'm hoping that more movies will come out that find their own stories and viewpoints. Blackness isn't just relegated to this one type of story. There's room for a lot of serious stuff. There's room for a lot of goofy stuff. We're human beings. We have plenty of different facets to show off. So I'm hoping things will just expand. The sky's the limit.

Coleman: I do think that something interesting is happening around the world-building. Some of it is influenced by gaming. Some of it is influenced by sci-fi. We’re going to become still more sophisticated, even in horror, and imagining new worlds that come out of our imagination. Some horror movies of the 1970s were a little bit derivative of the Classic Monsters. Dracula became Blacula. That kind of thing.

I think the next wave of horror perhaps is imagining new worlds and informed a little bit more by Afrofuturism. That means it won't always be grounded in, and it isn't always, but there will be less grounding in the relationship between Blackness and whiteness, as an example. What does a horror world look like? Where do we find the horrors, the anxieties, when that is stripped away?

If you were to recommend a few Black horror films to someone who's interested in learning more about the genre, which ones would you pick? I’m naturally assuming Night of the Living Dead and Get Out.

Harris: Yeah, those are those are givens. One of my favorites in recent years is actually from England, called His House that's on Netflix. It’s a movie about immigrants from Africa coming to England and moving into a haunted house. That was really great and surely should have been nominated for some Oscars. It was that good.

You could also go back and watch Blacula. You could say the original Black horror movie in terms of, at least in modern times, it was the first one that really had a Black cast, Black director, writer, everything. It was one of the early Blaxploitation movies and helped the Blaxploitation movement even beyond horror get a foothold. That's a really good one that still holds up today.

Coleman: I'm trying to distinguish between my favorites and something that is instructive. 100% agree with Blacula. The other is almost anything that's done by Spencer Williams would be super instructive.

Then, I have a favorite, Chloe, Love is Calling You from the 1940s, which when read through a contemporary liberal modern lens is surprisingly progressive, and not the sort of anti-Blackness treatise that you would think they tried to make it. So it has a Black star in Mandy. It has revenge and retribution. Spoiler alert, Mandy lives, but she's incarcerated. Imagine that.

The white people in the movie look really bad. This is a story of a Black woman who kidnaps a white child from a family who has lynched her husband. And it's a real interesting indictment on whiteness, though unintentional, because their racism is on full display. When Chloe comes back, they actually just by association think that she's Black, and say terrible, racist things about her. And she's their kin. But it also just reminds us how ridiculous racism is because she's white. And they say, “Oh, my God, she's so dark.” I love that line.

The actress Georgette Harvey, who is Mandy, was gay in real life and does an interesting, non-conforming gender portrayal, where she dresses as Baron Psalmody in the movie and takes on a kind of other performance. There's a lot of implicit messages in that movie that one would not have expected. If you're doing a cinema literacy class or film studies class, there's a lot there.

Do either of you have any upcoming projects?

Harris: We’re working together a little bit on one thing coming out. I wrote an essay for an anthology book that Robin is editing, I think it’s called, The Oxford Handbook of Black Horror. It looks at Black horror on a global scale. The book is collecting essays from different parts of the world about how Blackness is represented in the genre. I wrote an essay about Black horror in Brazil. It should be interesting.

---

To learn more about The Black Guy Dies First and to pick up a copy for yourself, visit: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Black-Guy-Dies-First/Robin-R-Means-Coleman/9781982186531

Photo Credits: Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman photo above is courtesy of Texas A&M University, Marketing and Communications. Mark H. Harris photo above is courtesy of Mark H. Harris.